1GW Cancer Center, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC

2Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC

3Department of Prevention and Community Health,

The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, Washington, DC

4Susan G. Komen, Dallas, TX

5Navegación de Pacientes International, Inc. (NPI), Boston, MA; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

6Patient Navigation Advisors – Independent Certified Oncology Navigator, Albuquerque, NM

7Patient Navigation Advisors – Independent Certified Oncology Navigator, Norwalk, CT

8Center for Deaf Health Equity, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC

Following decades of research demonstrating efficacy of patient navigation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established a rule to reimburse for patient navigation services for Medicare beneficiaries on January 1, 2024. This paper outlines how to credential your navigation team to ensure that you are set up for payment under the new G-codes for patient navigation. We outline a variety of ways to document that your navigation team is appropriately credentialed. We include what the CMS rule says and does not say in terms of credentialing and standards, and we include evidence-based, free resources to bolster your navigation team’s foundational knowledge base in preparation for using the new billing codes.

Following decades of research demonstrating efficacy of patient navigation,1-3 effective January 1, 2024, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) started paying for patient navigation under the CY 2024 Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule.4

What Are the Codes?

New codes are now available to pay for Principal Illness Navigation (PIN) for illnesses expected to be managed for 3 months or longer (G0023, G0024). PIN services can be performed by a patient navigator, community health worker (CHW), or other nonclinical healthcare staff working under the general supervision of a billing practitioner. Additional codes are available for Community Health Integration (G0019, G0022, G0511 for Federally Qualified Health Centers); PIN services by peers (G0140, G0146); and Social Determinants of Health Risk Assessment (G0136).

The rule reminds us that existing codes for clinical care management are still available, and these new codes do not replace those existing codes. For example, Chronic Care Management (99437, 99439, 99490, 99491), Complex Chronic Care Management (99487, 99489), and Principal Care Management (99424-99427) codes remain appropriate to bill for the management of patients with cancer or other chronic conditions that are reasonably expected to last 3 months or longer.5

The new G-codes for PIN may be used by auxiliary personnel, including CHWs, patient navigators, social workers, nurses, and any other qualified person performing navigation functions. Organizations may also contract with community-based organizations to provide and bill for these services.

What Is Principal Illness Navigation?

PIN services include a range of activities to assist patients with high-quality cancer care. Specific activities include providing person-centered assessments; facilitating patient-driven goals of care; providing support to help patients complete their treatment plan; coordinating services across healthcare, community, and social service providers; communicating with all providers to coordinate care; providing patient education; supporting patient self-advocacy; helping patients make appointments; facilitating behavior change; providing social and emotional support; and providing mentorship.5

Credentialing and Training Requirements for Payment

Qualifying for Medicare payment for PIN billing can be confusing. CMS defers to state-based credentialing requirements, which vary broadly from certification requirements to structured, rigorous training. The rule references the state-based requirements that are found in the C3 Project’s Community Health Worker Core Competencies Resource Guide, which can be downloaded free of charge.6

It is currently unclear whether cancer patient navigators need to fulfill their state’s CHW requirement given their more specific role in assisting cancer patients compared with the more general scope of practice of many CHWs. While it may be more than is required by CMS, it would be prudent for navigators to obtain CHW credentialing in their state and then document oncology-specific knowledge for practice. Greater clarity on cancer navigator requirements in states with CHW (but not navigation) credentialing standards will emerge as we gather lessons learned in implementing the new codes and receive future guidance from CMS.

If a state does not have a certification requirement, it is important to know that there is not a federal certification requirement to qualify for reimbursement. Nor is there a specific training or credentialing process that is endorsed by CMS. In the case of states without credentialing requirements, training in core competency domains must be documented:

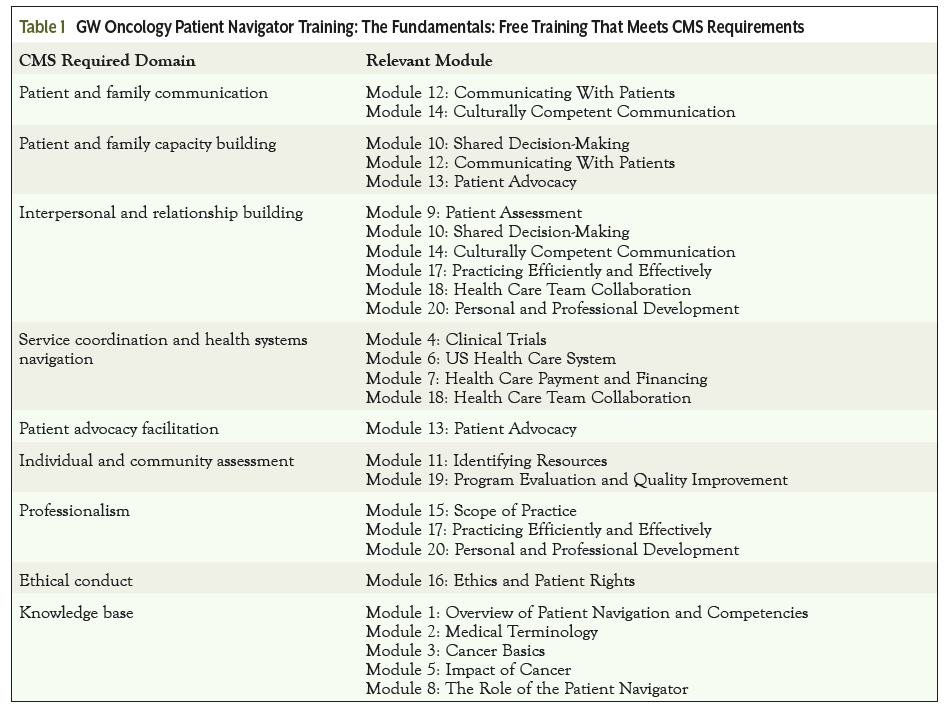

In States that do not have applicable licensure, certification, or other laws or regulations governing the certification or training of auxiliary personnel, we proposed to require auxiliary personnel providing PIN services be trained to provide all service elements. Training must include the competencies of patient and family communication, interpersonal and relationship-building, patient and family capacity building, service coordination and systems navigation, patient advocacy, facilitation, individual and community assessment, professionalism and ethical conduct, and the development of an appropriate knowledge base, including specific certification or training on the serious, high-risk condition/illness/disease addressed in the initiating visit.4

Institutions must demonstrate that patient navigators have received appropriate training and/or have demonstrated experience and skills in the relevant domains (see column 1 of Table 1). Additional training is required to ensure that CHWs and patient navigators have sufficient knowledge of the illness continuum relevant to their job role and scope of practice. For navigators performing nurse or social work roles, appropriate licensure for their profession should be documented in addition to navigation knowledge for practice.

CMS does not specify how to document training. For cancer patient navigators, there are many ways to document training: this might be done through a certificate of completion for a training that covers required competencies, or it could be demonstrated through a credential that assesses skills based on those competencies. For example, the Oncology Patient Navigator–Certified Generalist (OPN-CG) credential assesses knowledge in the required domains and additionally has practice requirements that document a certain level of experience.7 Currently, the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+) is updating the certification process for OPN-CG credentialing. However, given the domains on which navigators with this credential were tested, this certification demonstrates appropriate knowledge and skills in the domains required by CMS.

A no-cost option for training that aligns with CMS requirements is the GW Oncology Patient Navigation Training: The Fundamentals. This training was created in 2014, made freely available to the public in 2015.

A no-cost option for training that aligns with CMS requirements is the GW Oncology Patient Navigation Training: The Fundamentals. This training was created in 2014, made freely available to the public in 2015, and maintained with the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The training can be accessed at bit.ly/PNTraining. The GW training provides a certificate of completion as well as nursing continuing education units.8,9

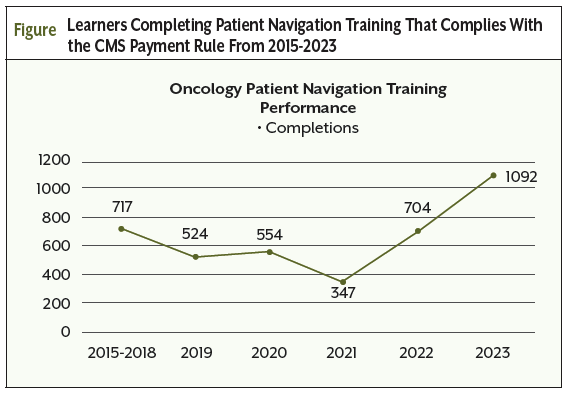

From 2015 through 2023, almost 4000 learners have completed the GW Oncology Patient Navigation Training directly via the GW Cancer Center’s Learning Management System, with over 1000 navigators completing the training in 2023 alone (Figure). An additional 393 learners registered for the training, and 106 new learners completed the training in the first month of 2024.

Do I Have to Pay for Training My Navigators?

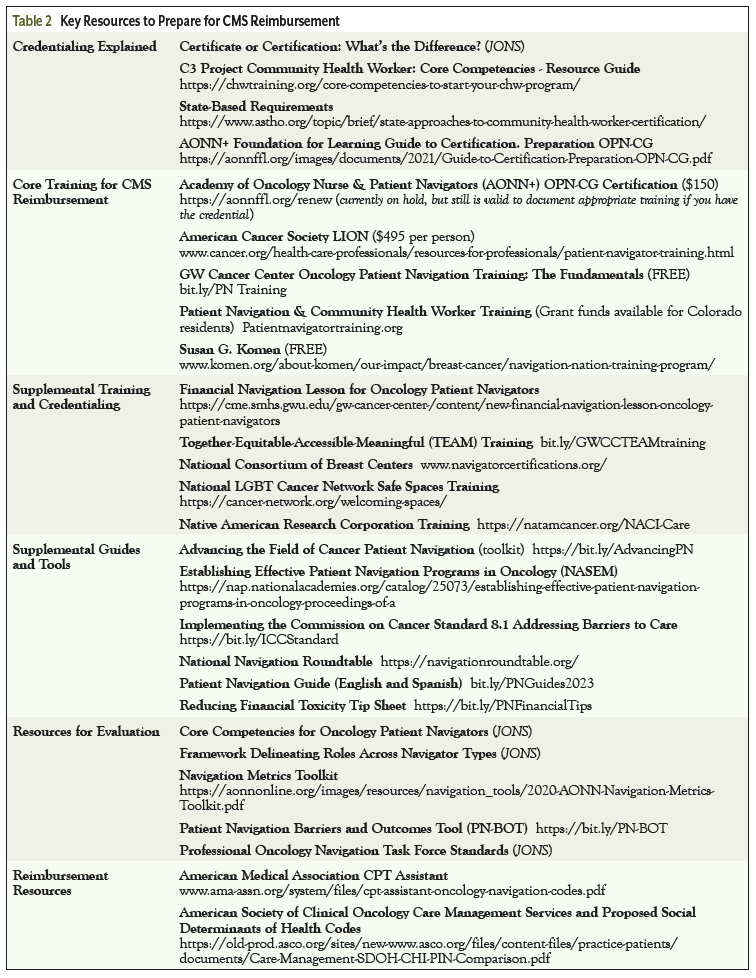

As previously mentioned, free training is available that meets CMS requirements. While other trainings may charge a fee for completion, the authors wish to emphasize that the required content to document appropriate training is freely available through evidence-based, enduring trainings from the GW Cancer Center and Susan G. Komen, as well as through decades-long state-specific efforts that may or may not have a fee, such as the Colorado Patient Navigation Collaborative.10 Further, there is no CMS requirement for certification at a national level. Finally, while there have been developments in the navigation field that provide helpful tools for implementing navigation in practice, it is critical to note that CMS does not endorse any particular organization’s standards beyond the competency domains listed previously. The exception to this is that PIN-Peer services specifically for evidence-based mental and substance abuse programs must document peer training based on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services standards.

We believe that no-cost education helps to level the playing field for navigators who may not have the financial resources to pay for training. Navigators who share lived experiences of patients are often better able to build rapport and establish credibility with patients. However, structural bias has historically excluded people of color, queer people, immigrants, and lower income individuals from accessing educational and career pathways for healthcare vocations. Free education reduces the risk of financial distress for navigators and supports a more diverse workforce that includes populations historically underrepresented in health careers.

Regardless of state requirements, the GW training is available to anyone with a desire to bolster knowledge of cancer, navigation role, and best practices and document their training for Medicare payment. The GW training has been shown to be efficacious with statistically significant learning improvements.11 It has been identified as a key resource to expand capacity for patient navigation in numerous state coalitions,12 state associations,13 and national organizations.14 For supplemental key resources, an update to our training is available at bit.ly/PNGuides2023.15 New guidance will be provided via the resources section of the training at least annually to ensure that learners have access to the most up-to-date information.

For supplemental key resources, an update to our training is available at bit.ly/PNGuides2023. New guidance will be provided via the resources section of the training at least annually to ensure the most up-to-date information.

Several regional and international organizations have adapted the GW training with appropriate permission and acknowledgment to tailor information for specific audiences. Susan G. Komen licensed the GW content and added original content, with 391 breast cancer navigators completing all modules and 2612 completing at least 1 course or workshop. Navegación de Pacientes International (NPI) has translated content from the GW Patient Navigation Guide into Spanish and has trained 59 navigators in Latin America. Currently, Abrale (Brazil Leukemia Lymphoma Society) is working on a Portuguese version of the training (J. Mourao, personal communication, September 20, 2023). Gallaudet University is evaluating an adaptation for deaf, deaf/blind, and hard of hearing learners who use American Sign Language (ASL) (P. Kushalnagar, personal correspondence, August 8, 2020); they have trained over 50 ASL-using deaf and hard of hearing learners nationwide, of whom a few were invited to participate as paid navigators for a National Institutes of Health–funded clinical trial cancer adherence study that targets deaf, deaf/blind, and hard of hearing patients who use ASL. The UHN Toronto Health System16-18 and the Indiana Veterans Administration19 have adapted content with permission to meet the needs of Canadian and Veteran navigators, respectively. The University of Houston Department of Social Work adapted the training to create a 3-hour undergraduate social work course at a federally designated, Hispanic- and Minority-serving institution (H. Goltz, personal communication, January 12, 2024). The Beyond Pink Foundation is currently adapting the curriculum for breast mentors (M. Guignard, personal communication, January 9, 2024). Finally, the World Health Organization references the GW training as a key resource in its Global Breast Health Initiative Technical Brief on Cancer Patient Navigation, forthcoming in 2024.20

GW training content may be adapted at no cost to customize information for your local context. PowerPoint decks covering most of the training content (sans videos) are freely available for your use and adaptation at bit.ly/PNGuides2023. Per general standards of academic integrity, please include the following acknowledgment if materials are accessed and adapted:

This content was adapted from the GW Cancer Center Oncology Patient Navigation Training: The Fundamentals (PI: Pratt-Chapman) developed and maintained by CDC cooperative agreements #NU38DP004972, #5NU58DP006461, and #NU58DP007539. Content added, changed, or adapted by our organization does not necessarily represent the views of the GW Cancer Center or the CDC.

The GW Cancer Center Oncology Patient Navigation Training: The Fundamentals, as well as the research that preceded it,8,9 and the supplemental resources that followed its launch (bit.ly/PNGuides2023) have been built through strong collaboration with the AONN+, the National Association of Social Workers, the Association of Oncology Social Work, the Oncology Nursing Society, the Association of Community Cancer Centers, and numerous community- based organizations and practicing navigators.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that appropriate training is the start, not the end, of effective navigation. Additional tools, such as those from the National Navigation Roundtable, the National Academies of Medicine, and the AONN+ provide guidance for navigation program implementation and quality improvement. Training and credentialing for specific populations, such as the National Consortium of Breast Centers certification program or the LGBT Cancer Network’s Welcoming Spaces training, provide strong documentation of knowledge for practice for breast-specific navigators.21 An ongoing commitment to learning, adequate institutional support, community partnerships, available resources to meet patient needs, and thoughtful implementation of programs bolster navigation excellence (Table 2).22,23

We hope that the GW Oncology Patient Navigation Training: The Fundamentals and the many free resources referenced within this article will kickstart your journey to CMS reimbursement for patient navigation. We are pleased to provide this free training to meet the needs of navigators and cancer centers across the United States. Further, we acknowledge the many thought leaders, researchers, navigators, and professional organizations who have contributed to the development of the training directly or indirectly through their professional expertise, research, and contributions to the field. Going forward, the field will benefit from sharing best practices and lessons learned as we collectively pilot and implement these new billing codes.

Funding Disclosure

The GW Oncology Patient Navigation Training and its supplementary resources are funded and maintained by CDC cooperative agreements #NU38DP004972, #5NU58DP006461, and #NU58DP007539 (PI: Pratt Chapman).

References

- Chan RJ, Milch VE, Crawford-Williams F, et al. Patient navigation across the cancer care continuum: an overview of systematic reviews and emerging literature. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:565-589.

- Kline RM, Rocque GB, Rohan EA, et al. Patient navigation in cancer: the business case to support clinical needs. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:585-590.

- Lopez D, Pratt-Chapman ML, Rohan EA, et al. Establishing effective patient navigation programs in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:1985-1996.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and Health and Human Services (HHS). Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2024 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicare Advantage; Medicare and Medicaid Provider and Supplier Enrollment Policies; and Basic Health Program. November 16, 2023. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/11/16/2023-24184/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2024-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Care Management Services and Proposed Social Determinants of Health Codes: A Comparison. 2023. https://old-prod.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/practice-patients/documents/Care-Management-SDOH-CHI-PIN-Comparison.pdf

- CHW training. Community Health Worker Core Competencies Resource Guide. 2022. https://chwtraining.org/core-competencies-to-start-your-chw-program/

- Pratt-Chapman ML. Oncology Patient Navigator–Certified Generalist: Learning Guides Are Here! Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2016;7(3).

- Willis A, Reed E, Pratt-Chapman ML, et al. Development of a framework for patient navigation: delineating roles across navigator types. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2013;4(6):20-26.

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Willis A, Masselink L. Core competencies for oncology patient navigators. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2015;6(2):16-21.

- PNCT: Patient Navigation & Community Health Worker Training. https://patientnavigatortraining.org/

- Kashima K, Phillips S, Harvey A, et al. Efficacy of the competency-based oncology patient navigator training. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2018;9:519-524.

- Kansas Cancer Partnership. Kansas Cancer Prevention and Control Plan: 2017-2021. 2017. www.kansashealthmatters.org/content/sites/kansas/Reports/Cancer/2017-2021_Kansas_Cancer_Plan.pdf

- North Carolina Oncology Navigator Association. Home Page. 2021. www.ncona.org/navigationprogramdevelopment.html

- Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators (AONN+). Oncology Patient Navigator Training: The Fundamentals. https://aonnonline.org/continuing-education/gw-cancer-center-opn-training-the-fundamentals

- GW Cancer Center. Update to Oncology Patient Navigator Training: The Fundamentals. 2024. https://cancercontroltap.smhs.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaskib661/files/2024-01/pn_guide_updates_1.12.2024.pdf

- Flora PK, Bender JL, Miller AS, et al. A core competency framework for prostate cancer peer navigation. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:2605-2614.

- Bender JL, Flora PK, Milosevic E, et al. Training prostate cancer survivors and caregivers to be peer navigators: a blended online/in-person competency-based training program. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:1235-1244.

- Bender JL, Flora PK, Soheilipour S, et al. Web-based peer navigation for men with prostate cancer and their family caregivers: a pilot feasibility study. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:4285-4299.

- Eliacin J, Matthias MS, Burgess DJ, et al. Pre-implementation evaluation of PARTNER-MH: a mental healthcare disparity intervention for minority veterans in the VHA. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48:46-60.

- World Health Organization Global Breast Cancer Initiative (in revision). Technical Brief on Breast Cancer Patient Navigation. www.who.int/initiatives/global-breast-cancer-initiative

- National Consortium of Breast Centers. Breast Navigator Certification Program. www.navigatorcertifications.org/certification/

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Willis A. Community cancer center administration and support for navigation services. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:141-148.

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Silber R, Tang J, Le PD. Implementation factors for patient navigation program success: a qualitative study. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2:141.