Clinical trials are critical for evaluating novel therapies and determining the best treatment strategies to enhance outcomes for patients with cancer. However, most clinical trials do not meet their enrollment targets due to both structural and clinical barriers.1 Studies have shown that 85% of patients receive their treatment in a community setting, resulting in up to 55.6% not participating in clinical trials because there are none available, while an additional 21.5% are eliminated due to eligibility criteria.1,2 To further compound the situation, clinical trial activities have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.3

Moving Past the Barriers

A Patient-Centric Decentralized Approach

A common structural barrier to clinical trial participation is the lack of available trials in the patient’s area. Most trials take place at research institutions and academic hospitals located in large metropolitan areas.1,4 This creates challenges for patients treated in the community setting, who have reported increased levels of emotional and financial stress when they are required to travel far distances to participate in these trials.1,4-6

A patient-centric, decentralized approach to clinical trials eliminates the need for patients to travel to the research site and is more representative of the larger population.3 When clinical trials struggle to meet targets for enrollment, the result can be prolonged completion times, which can make it more difficult for investigators to draw definitive conclusions.7 A blended approach of traditional clinical trials with the support of telemedicine and the incorporation of new digital health tools can extend the reach of highly controlled clinical investigations to patients in the community setting.5

Patient Selection at an Aggregate Level

In addition to structural barriers, the issue of clinical barriers must also be addressed. The treating oncologist’s primary focus is connecting with patients to offer them the most effective treatment options. In some instances, this may include discussions on clinical trial participation when appropriate. However, a recent survey found that although 50% of responding oncologists said that they were aware of the existence of available clinical trials, many indicated that it was a challenge to stay current on the status of these trials.8 As a result, patients with cancer are often unaware of clinical trials that they can participate in.1,9

There is also a misconception that only terminal patients choose to participate in clinical trials because they have no other options.1 In reality, trials often include therapies to treat cancer types with a high survival rate to evaluate alternative treatment options against standard therapy.3

Technology Solutions and Analytics

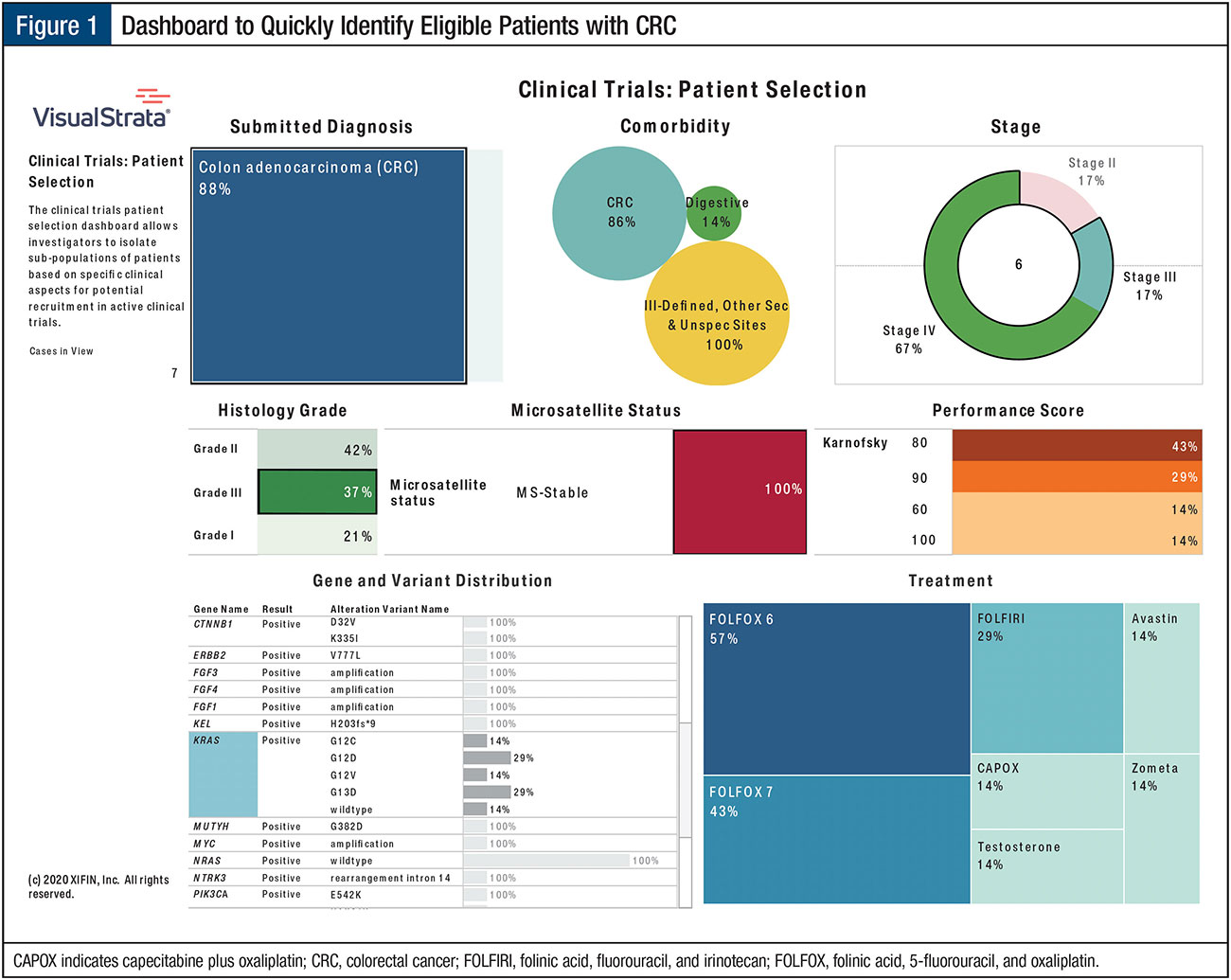

Implementing technology solutions and analytics that bring together all aspects of the patient record, including molecular test results, can facilitate aggregate patient availability across the practice. An example of how a community practice can utilize its data is shown in the clinical trials patient selection dashboard (Figure 1).

In this illustration, technology and analytics provide the tools to quickly identify the population of interest based on the following key indicators:

- Colorectal cancer

- High grade

- Unresectable

- KRAS with variant (ie, G12A, G12C, G12D, G13D)

- No microsatellite instability or microsatellite stability

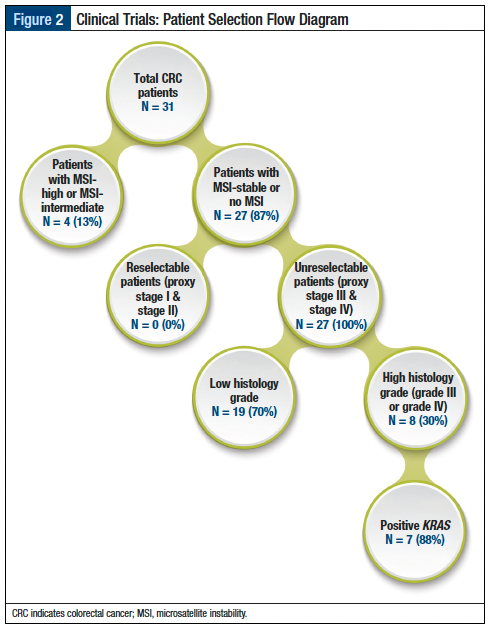

A common criticism of clinical trial designs is that the eligibility criteria are too restrictive, resulting in the unnecessary exclusion of patients due to strict study protocols-based procedures, which are not part of treatment standards in routine care.5 To evaluate the impact of this phenomenon, investigators can review other clinical attributes to determine how critical the procedure is to the study protocol and whether it should be used to exclude a particular patient. As shown in Figure 2, 70% of patients are not eligible for the trial and are therefore removed because they have a low histologic grade. The dashboard’s objective sampling could be utilized in feasibility studies to guide investigators on trial selection, so that participation would likely yield study enrollment and thus, avoid under-enrolling/not enrolling in a trial.

Conclusion

Clinical trials play an essential role in improving survival outcomes and quality of life for patients with cancer, yet there are structural and clinical barriers that need to be addressed. A decentralized approach can bring clinical trials to patients receiving treatment in the community setting and allow for the reflexibility of continued participation even during a pandemic. With the proper support and infrastructure to meet the many requirements needed to conduct a clinical trial, community-based oncology practices can begin to actively participate in and support these activities. Combining a patient-centric, decentralized approach with analytics allows principal investigators to drill down on their core population by cancer type and specific clinical characteristics, giving them an idea of their true population numbers. It also provides them the visibility in which criteria in their protocol eliminate the largest number of patients, allowing for future discussions on how critical that clinical component is for their study. The dashboard provides greater transparency into their target population and can be leveraged to inform active outreach and recruitment activities to clinical trial participation.

References

- Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:245-255.

- Bowen J. Busting patient recruitment bottlenecks in oncology trials. June 1,2020.www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/busting-patient-recruitment-bottlenecks-oncology-trials. Accessed October 16, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Advancing oncology decentralized trials. April 12, 2021. www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/advancing-oncology-decentralized-trials. Accessed October 12, 2021.

- Gould B. How one hospital is reaching rural patients for clinical trial recruitment. May 22, 2019. www.patientcentra.com/patient-recruitment-insights/reaching-rural-patients-clinical-trial-recruitment. Accessed October 16, 2021.

- Khozin S, Coravos A. Decentralized trials in the age of real-world evidence and inclusivity in clinical investigations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106:25-27.

- Gafford JA, Gurley-Calvez T, Krebill H, et al. Expanding local cancer clinical trial options: analysis of the economic impact of the Midwest Cancer Alliance in Kansas. Acad Med. 2017;2:1274-1279.

- Forster V. Why do only eight percent of cancer patients in the U.S. participate in clinical trials? February 19, 2019. www.forbes.com/sites/victoriaforster/2019/02/19/why-do-only-eight-percent-of-cancer-patients-in-the-u-s-participate-in-clinical-trials/?sh=1a43731977e9. Accessed October 12, 2021.

- Fenton L, Rigney M, Herbst RS. Clinical trial awareness, attitudes, and participation among patients with cancer and oncologists. Community Oncols. 2009;6:207-228.

- Copur MS. Inadequate awareness of and participation in cancer clinical trials in the community oncology setting. Oncology (Williston Park). 2019;33:54-57.