The site of cancer care has dramatically drifted away from community oncology practices, but innovation in the form of payment reform and the oncology medical home is being driven by community oncology practices, according to Ted Okon, MBA, Executive Director, Community Oncology Alliance.

“There is a dramatic shift in the site of care that’s fueling increased cost of cancer care,” said Mr Okon. “It’s just not sustainable,” Mr Okon said at the Sixth Annual Conference of the Association for Value-Based Cancer Care.

For example, between 2004 and 2014, the percentage of chemotherapy administered in community oncology practices decreased from 84.2% to 54.1%, whereas hospitals participating in the 340B drug discount program have increased their share of chemotherapy administration by 670% during the same period, from 3% to 23.1%.

Practice consolidation into the hospital side has been occurring for “push” and “pull” reasons, Mr Okon said. The “push” reasons include the declining payment for cancer care, administrative burdens on physicians, and obstacles to patients, such as Medicare and insurance company requirements.

On the “pull” side, Mr Okon noted hospitals cutting off cancer referrals to oncologists. “This is so perverse to me, because this impacts patient care,” he said. “This isn’t just a money issue.” Other causes of consolidation include the higher payments received by hospitals for identical services (ie, administering chemotherapy) and 340B drug discounts.

“The 340B program is a critical program for patients when it’s used by patients,” Mr Okon said. “If you look at the Ryan White HIV/AIDS clinics, if you look at the hemophilia clinics, if you look at the community health centers, they would not be able to provide the care they do without 340B discounts.”

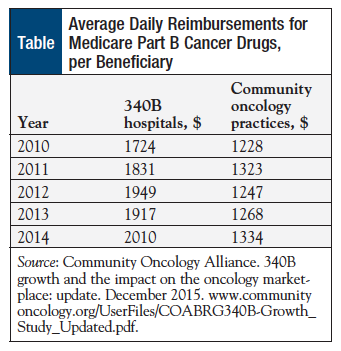

However, 62% of oncology drugs are administered in hospitals that participate in the 340B drugs program, with a proportionate increase in costs; hospitals participating in the 340B drugs cost Medicare 51% more than community oncology practices that do not participate in the program (Table).

Incentivizing High Drug Costs

The incentive for high margins on 340B drugs is the real issue, because it has the unintended consequence of rewarding hospitals versus community centers and leads to practice consolidation, given that hospitals find it economically beneficial to purchase cancer clinics, which results in higher costs for patients, Medicare, and taxpayers, said Mr Okon. But hospitals do not treat indigent populations—community practices do.

According to a Government Accountability Office report on 340B pricing in June 2015, “The financial incentive to maximize Medicare revenues through the prescribing of more or more expensive drugs at 340B hospitals also raises concerns….Not only does excess spending on Part B drugs increase the burden on both taxpayers and beneficiaries who finance the program through their premiums, it also has direct financial effects on beneficiaries who are responsible for 20 percent of the Medicare payment for their Part B drugs.”1

The problem with the financial incentives in the 340B drugs program is the question of “the appropriateness of care in terms of prescribing more, and more expensive drugs,” Dr Okon said.

Cancer drug costs contribute to the high cost of cancer care, but they are not the only factor in increasing costs; other cost drivers include big healthcare systems, cancer surgeries, radiation oncology, and inpatient admissions. The cost of biologic chemotherapy (including immunotherapy), in particular, is a prominent driver of the growing cost of cancer care.

Between 2004 and 2014, spending on biologic chemotherapy increased by 335% for the Medicare population and by 485% for the commercially insured patient population.

Innovation from Community Oncology Practices

When the US cancer care delivery system evolved from large academic centers to physician-run community cancer practices, it ushered in accessible affordable care.

As a result of the 340B program, hospitals’ motivation for change is blunted. For this reason, more innovation is coming from community oncology practices, Mr Okon said. He pointed to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pilot program, the Oncology Care Model (OCM), in which 70% of health systems have networked with university health systems, as one example of such innovation. The OCM pilot program has encouraged peer-to-peer information exchange through affinity groups and a dedicated listserv.

“We’re working on something called the OCM 2.0,” he said. “We don’t agree with everything on the OCM. I don’t think the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation agrees with everything, because it’s a pilot program.”

Reference

- US Government Accountability Office. Medicare Part B Drugs: Action Needed to Reduce Financial Incentives to Prescribe 340B Drugs at Participating Hospitals. June 2015. www.gao.gov/assets/680/670676.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2016.