The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) has placed even more emphasis on the common coding phrase, “If it isn’t documented, it can’t be reported.” The increased specificity of the new code set is about more than only capturing the laterality of a patient’s disease and the precise anatomical site. Assigning the correct diagnosis code is about more than only reporting the first payable diagnosis code. The impact of the reported codes extends beyond individual claim forms and will be felt for years ahead as the codes lay a foundation for the quality-based reimbursement systems of the not-so-distant future.

Coding for Specific Patient Populations

If a standard insurance claim form currently allows 12 diagnosis codes and an electronic format allows even more, then the goal is straightforward: describe the patient’s condition complete with comorbidities, underlying risk factors, and/or the socioeconomic conditions that influence the treatment or recovery of your patients. If providers are to be paid based on a metric that is focused on quality and outcome, the data need to clearly explain the nuances of the patient mix: very few patients simply have “cancer.”

Lung Cancer

For example, how many of your patients with lung cancer continue to smoke? Compare that general number with the precise number of times that code F17.2xx has been reported on an insurance claim form since October 1, 2015. There is a specific range of codes to report nicotine-induced disorders. These disorders include (but are not limited to) respiratory diseases and cancers (Example 1). Research clearly demonstrates that smoking increases a patient’s risk for cancer, but if the smoking status of a patient is reported at all, it is often downcoded to “uncomplicated.” This may be the result of the uncomplicated code being first in the drop-down box, but is more often the result of incomplete documentation within the provider’s progress notes.

The provider must document that the patient’s lung cancer is a result of the patient’s active or personal history of smoking. To list “current smoker” in the final assessment or to limit “smoking × packs a day” to the patient’s social history is insufficient.

Breast Cancer

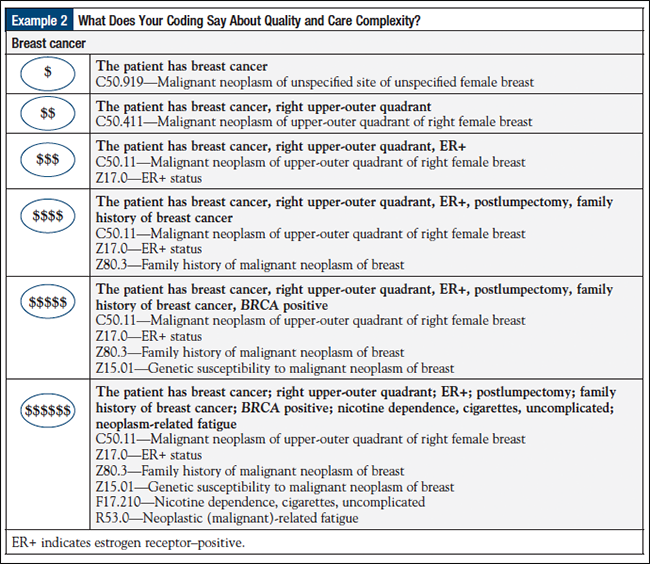

Another common cancer seen in oncology practices is breast cancer. Not all patients with breast cancer are equal. Patients’ estrogen receptor status impacts their treatment options and disease recurrence risks. If a patient also has a family history of breast cancer, the risk increases, and if he or she has a personal history of breast cancer or other related cancers, the recurrence risk increases even further. Too often a claim form will report only the patient’s primary condition. Using code C50.111 for malignant neoplasm of upper-outer quadrant of right female breast is more specific than using the unspecified code that was used in ICD-9-CM, but it does not communicate the patient’s true clinical picture (Example 2).

Cancer-Related Adverse Effects

Frequently, the history of the present illness and/or the assessment will document “pain.” ICD-10-CM requires that the location of the pain be documented as well, unless it is documented as “neoplasm-related pain” (code G89.3). There is a significant difference between back pain from yard work and overall pain from the patient’s disease and/or treatment.

A rash may simply be a reaction to a new bath soap, or, as is more likely in a patient with cancer, it could be a reaction to radiation treatment (code L58.9).

Each of the “routine” signs and symptoms that a patient with cancer may have during treatment is different from the same signs and symptoms of someone without cancer, so the diagnosis codes on your insurance claim form must communicate that difference. For example, does the patient have anemia or drug–induced anemia (code D64.9)?

Is that chemotherapy-induced neuropathy or diabetes-related neuropathy?

Coding Starts with Providers’ Accurate Documentation

Review the codes in the G62 code range to ensure that you are reporting the specific context for the condition that you are reporting. Remember, if it is not documented, it can’t be reported. If the progress note does not document the relationship between the patient’s conditions, a coder cannot draw the conclusion that the patient’s presenting symptoms are a result of chemotherapy. All providers need to understand the impact of incomplete assessment and plan sections.

The categorization of patients needs to be consistent among providers within the practice. There is much discussion about the category or status of patients with cancer, and the coding guidelines can only offer so much direction. At what point should a patient be reported to have a “personal history of x,” and for how long should the patient’s malignancy be reported as an active condition?

Unlike the clinical interpretation, coding guidelines consider that (1) if the site has been excised and/or eradicated, (2) if there is no further treatment at that site, and (3) if there is no evidence of disease, then that patient should be reported to have a “personal history of” that specific malignancy. The challenge is in agreeing on the definition of “active treatment” at a specific site. For example, is tamoxifen being prescribed to prevent a recurrence or to actively treat the disease? For specific drugs that can be used for these 2 categories, an agreement needs to be reached by the providers about the drug preference, and the outcome must be spelled out in the coding policy manual.

One measure currently used for defining quality of care is the patient’s posttreatment status. It is important to demonstrate that the revenue expended on a cancer treatment has transformed the patient into the “history of” status. All providers must understand the impact of the phrase “personal history of” within the context of their patient’s present illness and must clearly categorize malignancies as “active” or as a “personal history of” within their assessment and treatment plan.

The bottom line is that the details within the clinical record count. If the patient receives a prescription for a painkiller, the history of the present illness should clearly document the interval history of that pain since the last patient–provider encounter. When a review of systems documents positive findings, those findings should be addressed within the balance of the provider’s note, even if it is a recommendation to return to the patient’s primary care provider.

Proper documentation is needed when a specific treatment plan is chosen, or if medications are increased or decreased because of a patient’s underlying chronic condition; and how the patient’s use of insulin or another drug influences the current treatment plan. Even conditions that would otherwise be perceived as “nonclinical,” such as a “patient is noncompliant with medications due to financial reasons” (code Z91.12x), should be documented and reported, because this may explain why the outcome does not meet industry expectations.

ICD-10-CM has offered the tool for providers to more accurately describe the complexity of their patients’ diseases. ICD-10-CM provides the tools to defend the unique nuances of patients with cancer and to begin to build the database on which future policies and reimbursement schedules will be based. It is therefore shortsighted to only look for the payable diagnosis.