Supported through funding from

Although the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2020 meeting was held virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic, hundreds of abstracts, posters, and presentations were still made available to inform clinicians on the latest developments in the treatment of lung cancer. This publication features some of the key highlights from the meeting, which can be used to improve the management and care of patients with the disease.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Advanced NSCLC

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of death from cancer worldwide.1 The 2 main types of lung cancer are non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for between 80% and 85% of all new lung cancer diagnoses.2 Survival rates vary depending on the stage and the type of cancer when diagnosed. In the United States, more than half of patients (57%) are diagnosed with advanced (metastatic) lung cancer.3 The 5-year survival rate associated with metastatic NSCLC is 5.8%.3

Research regarding the management of patients with NSCLC that was presented at the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting ranged from studies of novel combinations of immunotherapy agents for metastatic NSCLC to assessments of targeted agents in patients with stage IB to stage IIIA epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated NSCLC.

3-Year Follow-Up Data for Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Treatment-Naïve NSCLC: The CheckMate-227 Trial

Researchers continue to explore the clinical efficacy of nivolumab (Opdivo; NIVO) combined with ipilimumab (Yervoy; IPI) in treatment-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC. In part 1 of the phase 3 CheckMate-227 study, first-line use of NIVO plus IPI was shown to significantly improve overall survival (OS) compared with chemotherapy, after a minimum follow-up of 29.3 months (P = .007).4 During the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting, the CheckMate-227 investigators reported data after a minimum 3-year follow-up.5

The CheckMate-227 trial enrolled treatment-naïve patients with NSCLC, including individuals whose tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression was ≥1% (for the primary analysis) or <1% (for the prespecified descriptive analysis).5 A total of 1189 patients with stage IV or recurrent NSCLC and PD-L1 expression of ≥1% were randomized to NIVO (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) plus IPI (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks), NIVO alone (240 mg every 2 weeks), or chemotherapy (pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin).5 Among 550 patients whose PD-L1 expression level was <1%, randomized treatments included NIVO plus IPI, NIVO (360 mg every 3 weeks) plus chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone.5

In patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥1%, the study’s primary end point was OS (NIVO plus IPI vs chemotherapy).5 At 6 months, an exploratory landmark analysis of OS was conducted according to patients’ response status: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease, and progressive disease.5

Data were locked on February 28, 2020, after a minimum follow-up for OS of 37.7 months.5 Among patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥1%, continued OS benefit was observed with NIVO plus IPI compared with chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67-0.93).5 The 3-year OS rates were 33% with NIVO plus IPI, 29% with NIVO monotherapy, and 22% with chemotherapy.5 At 3 years, 18% of patients with PD-L1 levels of ≥1% who were treated with NIVO plus IPI demonstrated progression-free survival (PFS), compared with 12% of those who received NIVO alone and 4% of those who received chemotherapy.5 Among confirmed responders with PD-L1 levels of ≥1%, 38% maintained duration of response (DoR) in the NIVO-plus-IPI arm at 3 years, compared with 32% in the NIVO arm and 4% in the chemotherapy arm.5

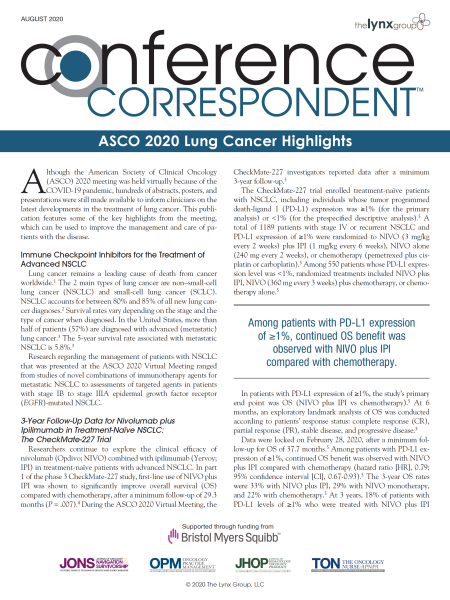

In patients with PD-L1 levels of <1%, the OS HR for NIVO plus IPI compared with chemotherapy was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.51-0.81; Figure 1).5 The 3-year OS rates were 34% with NIVO plus IPI, 20% with NIVO plus chemotherapy, and 15% with chemotherapy.5 In this cohort, 13%, 8%, and 2% of patients, respectively, reported PFS after 3 years.5 In addition, 34%, 15%, and 0% of confirmed responders, respectively, maintained a DoR after 3 years.5

Patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥1% who achieved either a CR or a PR at 6 months had a longer subsequent OS with NIVO plus IPI compared with chemotherapy alone, whereas those with stable disease or progressive disease at 6 months generally had a similar subsequent OS between treatments.5

Treatment-related adverse events (AEs) of any grade were observed in 77% of patients treated with NIVO plus IPI versus 82% of those who received chemotherapy.5 Severe (grade 3/4) treatment-related AEs were observed in 33% of patients treated with NIVO plus IPI and in 36% of patients undergoing chemotherapy.5 No new safety signals were identified with the combination therapy.5

The investigators concluded that after a 3-year minimum follow-up, NIVO plus IPI continued to provide durable, long-term efficacy benefits compared with chemotherapy in treatment-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of PD-L1 expression.5,6 This dual immunotherapy regimen is a novel chemotherapy-sparing, first-line treatment option for patients with advanced NSCLC.5

Adding Chemotherapy to NIVO plus IPI as First-Line for Advanced NSCLC: The CheckMate-9LA Trial

The combination of NIVO plus IPI has demonstrated improved OS versus chemotherapy in treatment-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC in CheckMate-227 part 1, regardless of PD-L1 expression.4 The researchers hypothesized that a limited course of chemotherapy added to NIVO plus IPI could provide rapid disease control and enhance the durable OS benefit observed with the PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitor combination.7 CheckMate-9LA was designed as a phase 3, randomized study to evaluate NIVO plus IPI plus 2 cycles of chemotherapy, compared with chemotherapy alone, as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV or recurrent NSCLC.7

In CheckMate-9LA, a total of 719 adults with treatment-naïve, histologically confirmed, stage IV/recurrent NSCLC were randomized to receive either NIVO (360 mg every 3 weeks) combined with IPI (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks) and 2 cycles of chemotherapy every 3 weeks (pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin for nonsquamous tumors, and paclitaxel plus carboplatin for squamous tumors) (N = 361) or 4 cycles of chemotherapy alone every 3 weeks (N = 358).7 Patients were stratified based on PD-L1 expression level (<1% vs ≥1%), sex, and histology (squamous vs nonsquamous).7 Chemotherapy in both study arms was selected based on tumor histology; those with nonsquamous NSCLC could receive pemetrexed maintenance in the chemotherapy-alone arm. Patients were treated with immunotherapy until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or for 2 years.7

The primary end point of CheckMate-9LA was OS. Secondary end points included PFS and objective response rate (ORR) by blinded independent central review, and efficacy according to PD-L1 subgroups. Exploratory end points included safety and tolerability.7

At a preplanned interim analysis with a minimum follow-up of 8.1 months, OS was significantly prolonged with NIVO plus IPI plus chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.69; 96.71% CI, 0.55-0.87; P = .0006).7 The addition of chemotherapy to NIVO plus IPI also was associated with statistically significant improvements in PFS and ORR.7

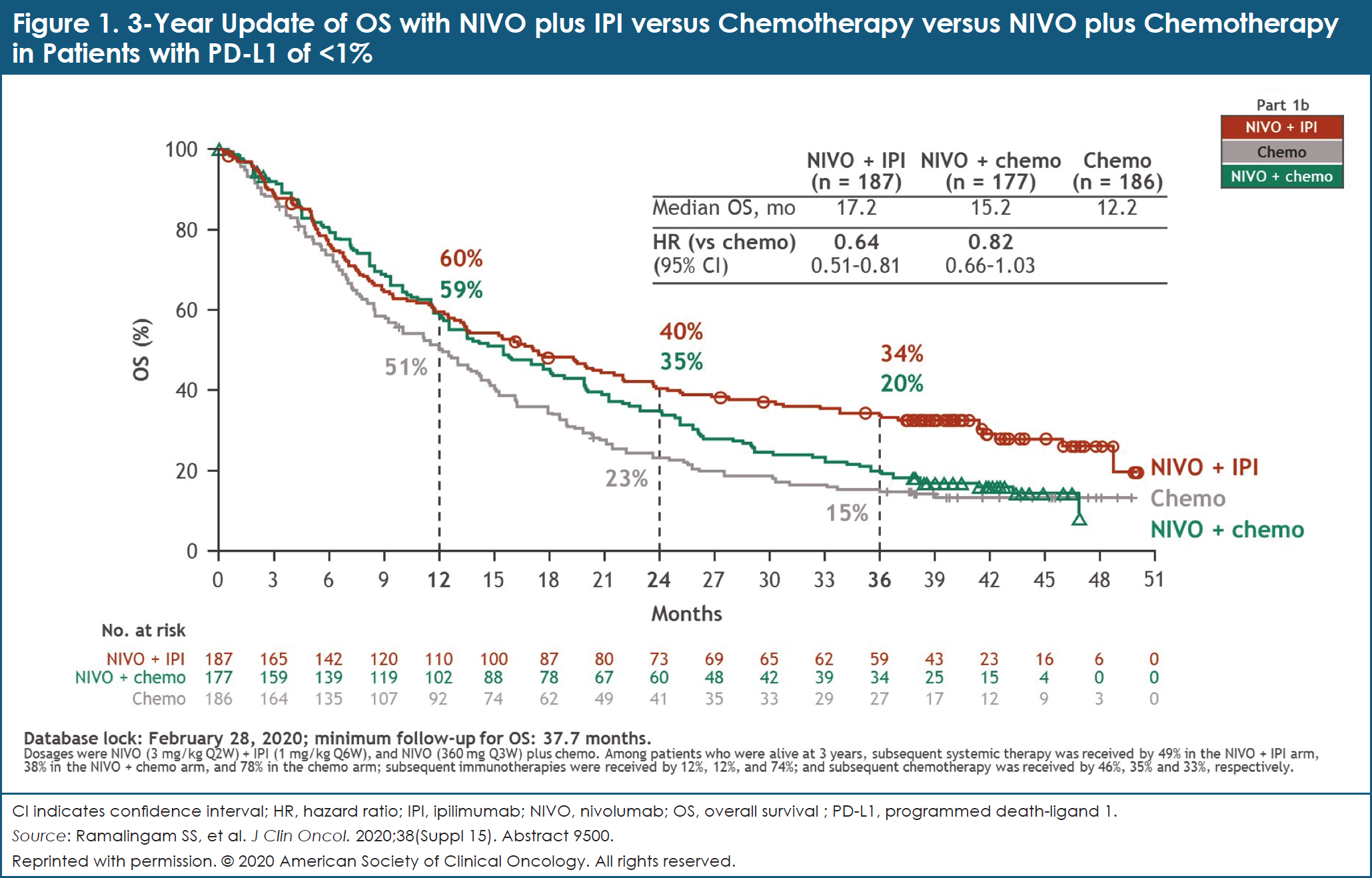

After a follow-up of at least 12.7 months, NIVO plus IPI plus chemotherapy continued to provide longer OS: the median OS with NIVO plus IPI plus chemotherapy was 15.6 months, compared with 10.9 months with chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.55-0.80).7 OS rates at 1 year were 63% and 47% with NIVO plus IPI plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone, respectively (Figure 2).7 Clinical benefit was consistent across all efficacy measures in key patient subgroups, including by PD-L1 expression level and tumor histology.7

Severe (grade 3/4) treatment-related AEs were reported in 47% of patients receiving NIVO plus IPI plus chemotherapy and in 38% of those receiving chemotherapy alone.7

The CheckMate-9LA investigators concluded that the study met its primary end point—a statistically significant improvement in OS was observed with NIVO plus IPI combined with a limited course of chemotherapy, compared with 4 cycles of chemotherapy alone, in patients with first-line advanced NSCLC. No new safety signals were reported. NIVO plus IPI combined with a limited course of chemotherapy should be considered as a new first-line treatment option for patients with advanced NSCLC.7

A Combination of NIVO, IPI, and Chemotherapy for Metastatic NSCLC: The CheckMate-568 Trial

In part 1 of the phase 2, single-arm CheckMate-568 study, NIVO plus IPI was shown to be effective and well-tolerated in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC.8 The researchers hypothesized that the addition of chemotherapy to dual immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy can further improve initial disease control. In part 2 of CheckMate-568, NIVO plus IPI combined with 2 cycles of chemotherapy was evaluated in patients with advanced treatment-naïve NSCLC.9

In part 2 of CheckMate-568, adult patients with untreated stage IV NSCLC received NIVO (360 mg every 3 weeks) plus IPI (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks) combined with 2 cycles of chemotherapy (pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin for nonsquamous tumors, and paclitaxel plus carboplatin for squamous tumors). This treatment was followed by NIVO plus IPI (without chemotherapy) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity for up to 2 years.9

The primary end points of the study were dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) within the first 9 weeks, safety, and tolerability. Treatment was considered safe if ≤25% of at least 22 evaluable patients experienced a DLT.9 DLTs included, but were not limited to, uncontrolled grade 3 nonskin treatment-related AEs, grade 4 treatment-related AEs, grade 2 treatment-related pneumonitis not resolved within 14 days, and treatment-related hepatic function abnormalities.9

A total of 36 patients received treatment, with most (97%) completing 2 cycles of chemotherapy combined with NIVO plus IPI.9 Three patients discontinued IPI while continuing treatment with NIVO.9 After a minimum follow-up of 26 months, only 1 (3%) patient experienced a DLT within the first 9 weeks—that is, transient, asymptomatic grade 3 aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase elevation.9

Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs occurred in 58% of patients. Overall, 22% of patients experienced a treatment-related AE of any grade that led to treatment discontinuation.9 These events, which included colitis, encephalopathy, pneumonitis, and arthralgia, occurred outside of the 9-week window for DLT assessment.9

The most common select treatment-related AEs, defined as AEs of potential immunologic causes, were skin-related and occurred in 50% of patients (any grade).9 The most common grade 3/4 select treatment-related AEs were endocrine (3 patients; 8%), and skin-related, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary (in 2 patients each; 6%).9 No treatment-related deaths were reported.9

The addition of 2 cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy to NIVO plus IPI showed encouraging clinical activity. The disease control rate was 89%, and the ORR was 47%.9 Median OS was 19.4 months.9

The investigators concluded that in patients with untreated advanced NSCLC, the addition of 2 cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy to NIVO plus IPI is effective and tolerable, with no unexpected safety signals.9 The phase 3 CheckMate-9LA study, discussed earlier in this publication, is also evaluating this combination regimen.7

Meta-Analysis of Checkpoint Inhibitor Trials in the First-Line Treatment of NSCLC

In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), ICI monotherapy, and the combination of chemotherapy plus ICI, have been shown to improve OS compared with chemotherapy alone in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.4,7 The benefit of chemotherapy plus ICI compared with ICI monotherapy, however, remains unknown.10

To explore this question, researchers conducted a systematic review of the medical literature using the MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases to identify relevant studies that were conducted through December 2019.10 Phase 3 RCTs that evaluated the efficacy of first-line ICIs or chemotherapy plus ICI, and that reported outcomes stratified by PD-L1 expression level status (<1%, 1%-49%, and ≥50%), were included in the analysis. ICI was defined as a single-agent PD-1 inhibitor or dual checkpoint blockade with a PD-1 inhibitor plus a CTLA-4 inhibitor. For patients with PD-L1 levels <1%, the study comparator was NIVO plus IPI. For patients with PD-L1 levels of 1% to 49% and PD-L1 levels >50%, study comparators included NIVO plus IPI and ICI monotherapy. Efficacy data included OS, PFS, and ORR.10

Among 7971 RCTs that were screened, 10 phase 3 RCTs were analyzed.10 These studies involved a total of 7218 patients who were assigned to either ICI (pembrolizumab [Keytruda], atezolizumab [Tecentriq], or NIVO plus IPI) or chemotherapy plus ICI (platinum-doublet plus atezolizumab, pembrolizumab, or NIVO).10 In patients with PD-L1 levels of <1%, a network meta-analysis that compared chemotherapy plus ICI with NIVO plus IPI failed to demonstrate a significant difference in OS, PFS, or ORR between the 2 treatments.10

In patients whose PD-L1 levels were between 1% and 49%, no significant difference in OS or ORR was reported between chemotherapy plus ICI and ICI monotherapy. PFS could not be analyzed because of lack of available data.10 In patients whose PD-L1 levels were ≥50%, chemotherapy plus ICI was associated with improved PFS (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.88) and ORR (odds ratio, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.20-3.50), compared with ICI monotherapy.10 No difference was reported, however, in the OS with chemotherapy plus ICI versus ICI monotherapy (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.66-1.30).10

The investigators concluded that although the addition of chemotherapy to ICI appears to improve ORR and PFS compared with ICI monotherapy in patients with PD-L1 levels ≥50%, chemotherapy plus ICI does not confer an OS benefit in the first-line treatment of patients with NSCLC, regardless of PD-L1 status. Prospective trials that compare chemotherapy plus ICI, ICI monotherapy, and combination ICI therapies are needed to confirm these findings.10

Characteristics of Patients Who Achieve Long-Term Response with PD-1 Blockade

To learn more about the frequency, characteristics, and predictors of long-term response to PD-1 inhibitors, patients from 2 institutions—Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC] in New York City and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute [DFCI]) in Boston, MA—who had been diagnosed with advanced NSCLC and treated with anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 therapy were examined.11 Responses were assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Long-term responders experienced PRs or CRs that lasted for ≥24 months. Short-term responders experienced PRs or CRs that lasted for <12 months. Comparisons were also made with patients who had progressive disease. PD-L1 expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was assessed by targeted next-generation sequencing. High TMB was defined as greater than or equal to the median of the cohort.11

Among 2382 patients, 6.3% (95% CI, 5.3%-7.4%) were considered long-term responders, with similar rates in both the MSKCC and DFCI cohorts.11 Short-term responses occurred in 6% of patients in the MSKCC cohort and 7% of those in the DFCI cohort.11 OS was longer among long-term responders compared with short-term responders (19.6 months vs median not reached, respectively; HR, 0.07; P <.001 in the MSKCC cohort; 18.0 months vs median not reached, respectively; HR, 0.08; P <.001 in the DFCI cohort).11 Long-term responders experienced deeper responses than short-term responders (median best overall response, –75% vs –39%; P <.001 and –71% vs –38%; P <.001, respectively).11 The rate of long-term response was higher among patients with high TMB and high PD-L1 compared with those with low TMB and low PD-L1 (16% vs 2%, respectively; P <.001).11

Overall, 2% of patients with sensitizing EGFR mutations (N = 243) achieved a long-term response to PD-1 inhibition.11 Loss-of-function variants in ARID1A (14% vs 2%), PTEN (8% vs 0%), and KEAP1 (12% vs 2%) were enriched in long-term responders compared with short-term responders (P <.05 for each).11 Among patients with KRAS mutations, the rate of long-term response was higher in those with co-mutation with TP53 compared with STK11 (12% vs 2%; P = .01).11

The investigators concluded that long-term response—defined as ongoing response for ≥24 months—to PD-1 blockade is an uncommon, but profound clinical outcome in patients with metastatic lung cancer. High TMB correlates with long-term response. The combination of high TMB and high PD-L1 was enriching for long-term responders but not for short-term responders. Features that predict long-term response may be distinct from those that are predictive of short-term (ie, initial) response.11

Patterns of Acquired Resistance in Patients with NSCLC Who Receive PD-1 Inhibitors

Researchers at MSKCC evaluated all patients with NSCLC who were treated with PD-1 blockade, to determine the frequency and patterns of acquired resistance to therapy.12 Acquired resistance was defined as initial response—either CR or PR—using RECIST criteria, followed by disease progression or death. Two different patterns of acquired resistance—“oligo” and “systemic”—were also defined. Oligo refers to progression in ≤2 sites of disease, whereas systemic is defined as progression in ≥3 sites of disease.12

Of 1201 patients with NSCLC who underwent treatment with PD-1 inhibitors, approximately 20% achieved initial response and 74% eventually had acquired resistance.12 Onset of acquired resistance was variable and decreased with a longer DoR: 53% progressed within 1 year, 37% progressed within 1 to 2 years, and 6% progressed after 2 years.12

Patients with PD-L1 expression levels of <50% and TMB of <8 mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) were more likely to have acquired resistance, compared with those with PD-L1 expression levels of ≥50%, and TMB of ≥8 mut/Mb (P = .02).12 Acquired resistance was frequently observed in lymph nodes (41%) and less often in the liver (6%).12

Patterns of acquired resistance were most often oligo (56%) rather than systemic (28%). Overall, 16% of patients died without evidence of radiographic progression.12 Oligo-acquired resistance occurred later, with a median onset of 12.9 months, compared with 5.6 months for systemic-acquired resistance.12 Oligo-acquired resistance also correlated with higher postprogression survival (median OS of 55.2 months vs 9.2 months with systemic-acquired resistance; P <.001).12 Postprogression OS was highest in patients with acquired resistance and a CR or PR, compared with those with initial stable disease or progression after PD-1 blockade (median OS, 18.9 months vs 12.5 months vs 4.4 months, respectively; P <.001).12 Of 49 patients who were initially treated with locally directed therapy for acquired resistance, 57% remain alive and systemic therapy-free.12

The researchers concluded that acquired resistance to PD-1 inhibition is common among patients with NSCLC. The risk for acquired resistance is lower in biomarker-enriched patients and as the DoR increases. Acquired resistance is frequently oligo in nature. Locally directed therapy is viable for oligo resistance and can improve survival outcomes. Acquired resistance appears to have a distinct biology compared with primary refractory disease, based on differences in organ-site distribution and postprogression survival findings.12

Anti-TIGIT Antibody Tiragolumab plus Atezolizumab in Patients with PD-L1–Selected NSCLC

T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif domains (TIGIT) is a recent immune checkpoint that is being investigated as an emerging target in cancer immunotherapy. TIGIT is an inhibitory immune checkpoint that is expressed on activated T-cells and natural killer T-cells in multiple types of cancer, including NSCLC.13

In the phase 1 GO30103 study, co-inhibition of TIGIT and PD-L1 signaling with tiragolumab plus atezolizumab in patients with chemoimmunotherapy-naïve, PD-L1–positive NSCLC improved ORR compared with historical ORR data with PD-L1 and PD-1 inhibitors.14 The researchers conducted a phase 2, randomized trial, called CITYSCAPE, to confirm the efficacy and safety of tiragolumab plus atezolizumab, compared with placebo plus atezolizumab, as first-line therapy in NSCLC.14

CITYSCAPE is a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Patients could enroll in the trial if they had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1; NSCLC with squamous or nonsquamous histology; no previous systemic therapy for locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic disease; and PD-L1 expression, as assessed by 22C3 immunohistochemistry by local or central assay. Patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) or EGFR mutations were excluded from the trial.14

Patients were randomized to tiragolumab (600 mg intravenous [IV]) plus atezolizumab (1200 mg IV) or placebo plus atezolizumab (1200 mg IV) on day 1 of every 3-week cycle.14 Stratification factors included PD-L1 status (tumor proportion score [TPS] ≥50% vs TPS 1%-49%), histology, and tobacco history.14 Co-primary end points were investigator-assessed ORR and PFS. Secondary end points included DoR, OS, and safety. Exploratory end points were the effect of PD-L1 status on ORR and PFS.14

A total of 135 patients enrolled in the trial and were randomized to tiragolumab plus atezolizumab (N = 67) or placebo plus atezolizumab (N = 68).14 More than half of all patients in both study arms had a PD-L1 TPS of 1% to 49% (57% each) and nonsquamous histology (60% vs 59%, respectively).14 At the time of primary analysis, treatment with tiragolumab plus atezolizumab was associated with a 43% reduction in the risk for disease progression or death compared with atezolizumab plus placebo (stratified HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37-0.90).14 With an additional 6 months of follow-up, improvement in PFS was maintained, with a median PFS of 5.6 months versus 3.9 months, respectively (stratified HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.38-0.89).14 At the primary analysis, ORR in the tiragolumab-plus-atezolizumab arm was almost twice that in the placebo-plus-atezolizumab arm—31% versus 16%, respectively.14 Updated analysis confirmed the ORR in both groups—37% versus 21%, respectively.14

In an exploratory analysis of 58 patients with high PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥50%), a 70% reduction in the risk for disease progression or death was reported with tiragolumab plus atezolizumab versus placebo plus atezolizumab (stratified HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.15-0.61).14 The median PFS in patients with high PD-L1 expression was not evaluable with tiragolumab plus atezolizumab, compared with 4.1 months with placebo plus atezolizumab.14 ORRs for patients with high PD-L1 expression (ie, ≥50%) were 66% and 24%, respectively.14

In the safety population (tiragolumab plus atezolizumab, placebo plus atezolizumab), any-cause AEs occurred in 99% and 96% of patients, respectively.14 Grade ≥3 AEs were reported in 48% of patients treated with tiragolumab plus atezolizumab versus 44% of those treated with placebo plus atezolizumab.14 AEs that led to treatment withdrawal occurred in 10% and 9% of patients, respectively.14

The investigators concluded that treatment with the anti-TIGIT antibody tiragolumab plus atezolizumab compared with placebo plus atezolizumab demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in ORR and PFS. The safety profile of tiragolumab plus atezolizumab was similar to that with placebo plus atezolizumab.14

Targeted Therapies for Advanced NSCLC

Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients with HER2-Mutated Advanced NSCLC

[Fam-] trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu; T-DXd) is an antibody–drug conjugate that comprises an anti-HER2 antibody, a cleavable tetrapeptide-based linker, and a potent topoisomerase I inhibitor payload. In a small phase 1 trial, patients with HER2-mutated NSCLC who received T-DXd had a confirmed ORR of 72.7%.15

DESTINY-Lung01 is an ongoing, open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study of T-DXd in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC who overexpress HER2 or have an HER2-activating mutation.16 Researchers reported data for the cohort of 42 patients with HER2 mutations after a median follow-up of 8.0 months (range, 1.4-14.2 months).16

In DESTINY-Lung01, patients were treated with T-DXd 6.4 mg/kg every 3 weeks. The primary end point was confirmed ORR (CR + PR) by independent central review.16 Additional end points included disease control rate (CR + PR + stable disease), DoR, PFS, and safety.16

At the time of data cutoff—November 25, 2019—a total of 42 (64.3% female) patients had received T-DXd.16 The median patient age was 63 years (range, 34-83 years).16 Nearly half (45.2%) had central nervous system (CNS) metastases.16 Most of the patients (76.2%) had an ECOG PS of 1.16 HER2 mutations were predominantly in the kinase domain (90.5%).16 Overall, 90.5% of the patients had received platinum-based chemotherapy, and 55% had received anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 treatment.16 The median number of previous treatment lines was 2 (range, 1-6).16

The median duration of treatment with T-DXd was 7.8 months (range, 0.7-14.3 months), and 45% of patients remained on treatment.16 The confirmed ORR was 61.9% (95% CI, 45.6%-76.4%).16 Median DoR was not reached at the data cutoff; 16 of 26 responders remained on treatment.17 See Figure 3 for best change in tumor size.16 The disease control rate was 90.5% (95% CI, 77.4%-97.3%).16 Estimated median PFS was 14.0 months (95% CI, 6.4-14.0 months).16

All of the 42 patients enrolled in the study experienced TEAEs; 64% were grade ≥3, of which 52% were drug-related, including decreased neutrophil count and anemia.16 Five (12%) cases of drug-related interstitial lung disease (ILD) were reported, as determined by an independent adjudication committee (all grade 2, no grade ≥3); 1 case of grade 1 ILD is pending adjudication.16 TEAEs led to dose interruption in 59.5% of patients, dose reduction in 38.1% of patients, and treatment discontinuation in 23.8% of patients.16

The researchers concluded that T-DXd demonstrated promising clinical activity, with a high ORR and durable responses in patients with HER2-mutated NSCLC. The safety profile was generally consistent with that of previously reported studies.16

Stage III NSCLC

Impact of Immune-Related AEs on Checkpoint Inhibitor Consolidation Therapy in Stage III NSCLC

Consolidation checkpoint inhibitor therapy for up to 1 year following chemoradiation is a current standard of care for patients with inoperable stage III NSCLC.17 The occurrence of immune-related AEs, however, may prevent some patients from completing the full year of consolidation checkpoint inhibitor therapy.18

To better understand the association between immune-related AEs and efficacy outcomes, researchers assessed data from the HCRN LUN 14-179 study—a single-arm, phase 2 trial of consolidation pembrolizumab therapy following concurrent chemoradiation in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC.18 In this trial, eligible patients with stage III NSCLC who did not progress after completion of chemoradiation received pembrolizumab 200 mg IV every 3 weeks for up to 1 year.18 Demographics, disease characteristics, and number of cycles of pembrolizumab received were reported in patients with any-grade immune-related AEs, except pneumonitis that included grade >2 only (Group A) and those without immune-related AEs (except grade 1 pneumonitis; Group B).18

A total of 92 patients were eligible for efficacy analysis.18 These patients were enrolled in the study from March 2015 to November 2016.19 The 4-year OS estimate for all patients was 46.2%.18 Any-grade immune-related AEs (except grade 1 pneumonitis; N = 37) included pneumonitis (18.5%), hypothyroidism (14.1%), hyperthyroidism (10.9%), increased creatinine (5.4%), elevated transaminases (3.3%), and colitis (3.3%).18 Grade ≥2 immune-related AEs (N = 32) included pneumonitis (18.5%), hypothyroidism (10.8%), and colitis (3.3%).18

The median number of pembrolizumab cycles received in patients in Group A and Group B were 9 and 14, respectively (P = .15).18 Four-year efficacy end points in Group A and Group B were time to metastatic disease (35.3% vs 41.3%, respectively; P = .83), PFS (27.8% vs 28.7%, respectively; P = .97), and OS (43.5% vs 47.9%, respectively; P = .99).18

The researchers concluded that even though they received fewer cycles of consolidation pembrolizumab, patients with stage III NSCLC who experienced any-grade immune-related AEs, excluding grade 1 pneumonitis, did not experience significantly reduced efficacy outcomes.18

Early-Stage NSCLC

Osimertinib as Adjuvant Therapy for EGFR-Mutated NSCLC: ADAURA Trial

Approximately 40% of patients with NSCLC present with localized or regional disease.3 Adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care in patients with resected stage II to stage III NSCLC and select stage IB patients, but disease recurrence can happen.19

Osimertinib (Tagrisso), a third-generation CNS-active, EGFR-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been approved for use in patients with advanced NSCLC.20 ADAURA is a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study that assessed the efficacy and safety of osimertinib versus placebo in patients with stage IB to stage IIIA EGFR-mutated NSCLC after complete tumor resection and adjuvant chemotherapy, when indicated.20 Following recommendations of an independent data monitoring committee, the trial was unblinded early because of efficacy.20 This report summarizes an unplanned interim data analysis.20

Eligible patients needed to be ≥18 years of age (≥20 years of age in Japan and Taiwan); have a World Health Organization PS of 0 or 1; primary nonsquamous stage IB, II, or IIIA NSCLC; confirmed EGFR mutation (either exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R substitution); and complete resection of primary NSCLC with full recovery from surgery.20 Postoperative chemotherapy was allowed. The maximum interval between surgery and study randomization was 10 weeks without adjuvant chemotherapy and 26 weeks with adjuvant chemotherapy.20

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to osimertinib 80 mg once daily orally or placebo and received treatment for up to 3 years.20 All patients were stratified by disease stage (IB, II, IIIA), mutation type (exon 19 deletion, exon 21 L858R substitution), and race (Asian, non-Asian).20 The primary end point of the study was disease-free survival (DFS), by investigator assessment, in patients with stage II to IIIA disease. Secondary end points included OS and safety.20

A total of 682 patients were randomized to treatment—339 to osimertinib and 343 to placebo.20 Baseline characteristics were balanced between the arms: stage IB, 31%/31% (osimertinib/placebo); stage II/IIIA, 69%/69%; female, 68%/72%; exon 19 deletion, 55%/56%; and exon 21 L858R substitution, 45%/44%.20 Overall, 55% of patients who received osimertinib and 56% of patients who received placebo had received adjuvant chemotherapy prior to study randomization.20

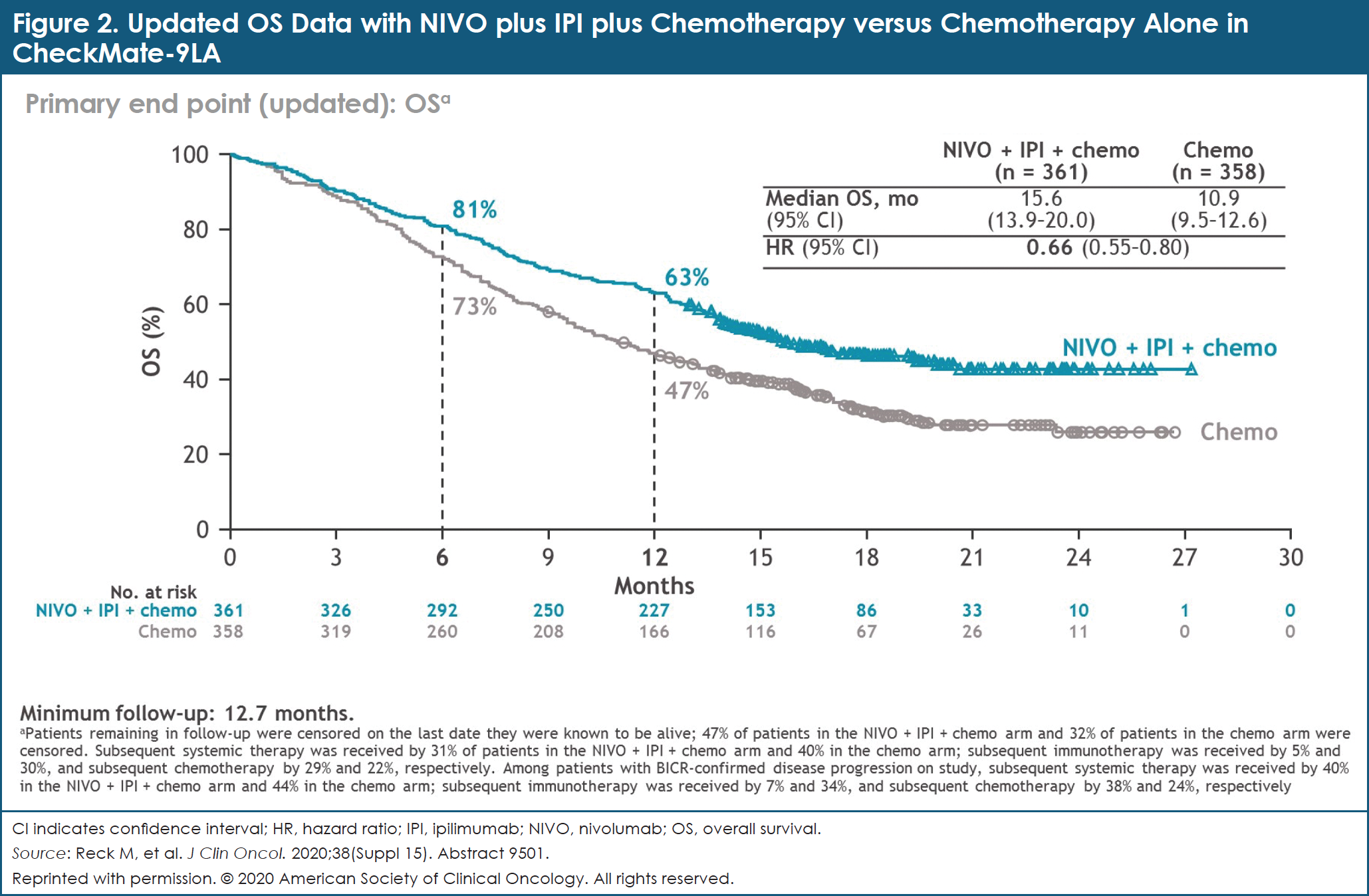

In patients with stage II and stage IIIA NSCLC, the DFS HR was 0.17 in favor of osimertinib, compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.12-0.23; P <.0001; Figure 4).20 The 2-year DFS rate was 90% with osimertinib versus 44% with placebo.20 In the overall population, the DFS HR was 0.21 (95% CI, 0.16-0.28; P <.0001).20 The 2-year DFS rate was 89% with osimertinib compared with 53% with placebo.20 OS data were immature at the time of data cutoff.20 The safety profile of osimertinib was consistent with that in prior reports.20

The investigators concluded that adjuvant osimertinib is the first targeted agent evaluated in a global trial to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in DFS in patients with stage IB, stage II, and stage IIIA EGFR-mutated NSCLC after complete tumor resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (when indicated). Adjuvant osimertinib offers an effective new treatment strategy for these patients with early-stage disease.20

Immunotherapy Combined with Stereotactic Radiation in Early-Stage, Medically Inoperable NSCLC: Safety Analysis from I-SABR

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) provides at least 95% local control in patients with medically inoperable early-stage NSCLC.21 These patients, however, can still experience recurrence in regional lymph nodes or distant organs, or secondary lung cancer.21 Combining immunotherapy with SABR may reduce these disease recurrences by stimulating a stronger cancer-specific immune response.22

I-SABR is an ongoing phase 2, randomized study comparing SABR with immunotherapy plus SABR to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of immunotherapy plus SABR in patients with medically inoperable, early-stage (T1 to T3: <7 cm, including multiprimary tumors), isolated-recurrence NSCLC without lymph node or distant metastasis.22 The primary end point of the I-SABR trial is event-free survival, with an event defined as any recurrence and/or death. Secondary research end points include rates of grade ≥2 toxicity. Four-dimensional computed tomography image-guided SABR (50 Gy in 4 fractions or 70 Gy in 10 fractions) was delivered to all patients.22 Patients randomized to I-SABR also received concurrent NIVO 240 mg IV every 2 weeks for a total of 7 doses or 480 mg every 4 weeks for a total of 4 doses.22 Researchers anticipate that 140 patients will enroll in I-SABR.22

To date, 92 patients have enrolled in I-SABR.22 The median patient age was 72 years (range, 57-90 years).22 These patients were randomized to SABR (N = 47) or immunotherapy plus SABR (N = 45).22 After median follow-up of 14.5 months (range, 2-28 months), no treatment-related grade 4 or grade 5 treatment-related AEs were reported.22 In the immunotherapy plus SABR arm, there was 1 case each of possibly related dyspnea (grade 3) and skin rash (grade 3), and 2 cases of probably related fatigue (grade 3).22 Other possible or probable treatment-related AEs included 2 cases each of grade 2 pneumonitis, fatigue, and pruritus, and 1 case each of grade 2 hyperthyroidism and arthralgia.22 No patients discontinued treatment due to AEs.22 Among patients who received SABR, possible treatment-related AEs included 1 case of fatigue (grade 2) and 1 patient with pneumonitis. All symptoms resolved.22

The investigators summarized this research by stating that the combination of NIVO with SABR appears to be well tolerated. In this study, the major barrier for patient enrollment and/or randomization has been patients’ concerns about potential toxicities and additional clinic visits. Continued enrollment and additional follow-up time are planned, to validate these safety findings.22

Advanced SCLC

SCLC accounts for approximately 10% to 15% of all new lung cancer diagnoses and carries a poorer prognosis.2 During the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting, studies regarding the management of patients with SCLC evaluated combinations of immunotherapy agents with chemotherapy, as well as novel combinations of targeted agents for patients with specific genetic mutations.

Addition of Durvalumab to Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in the CASPIAN Study

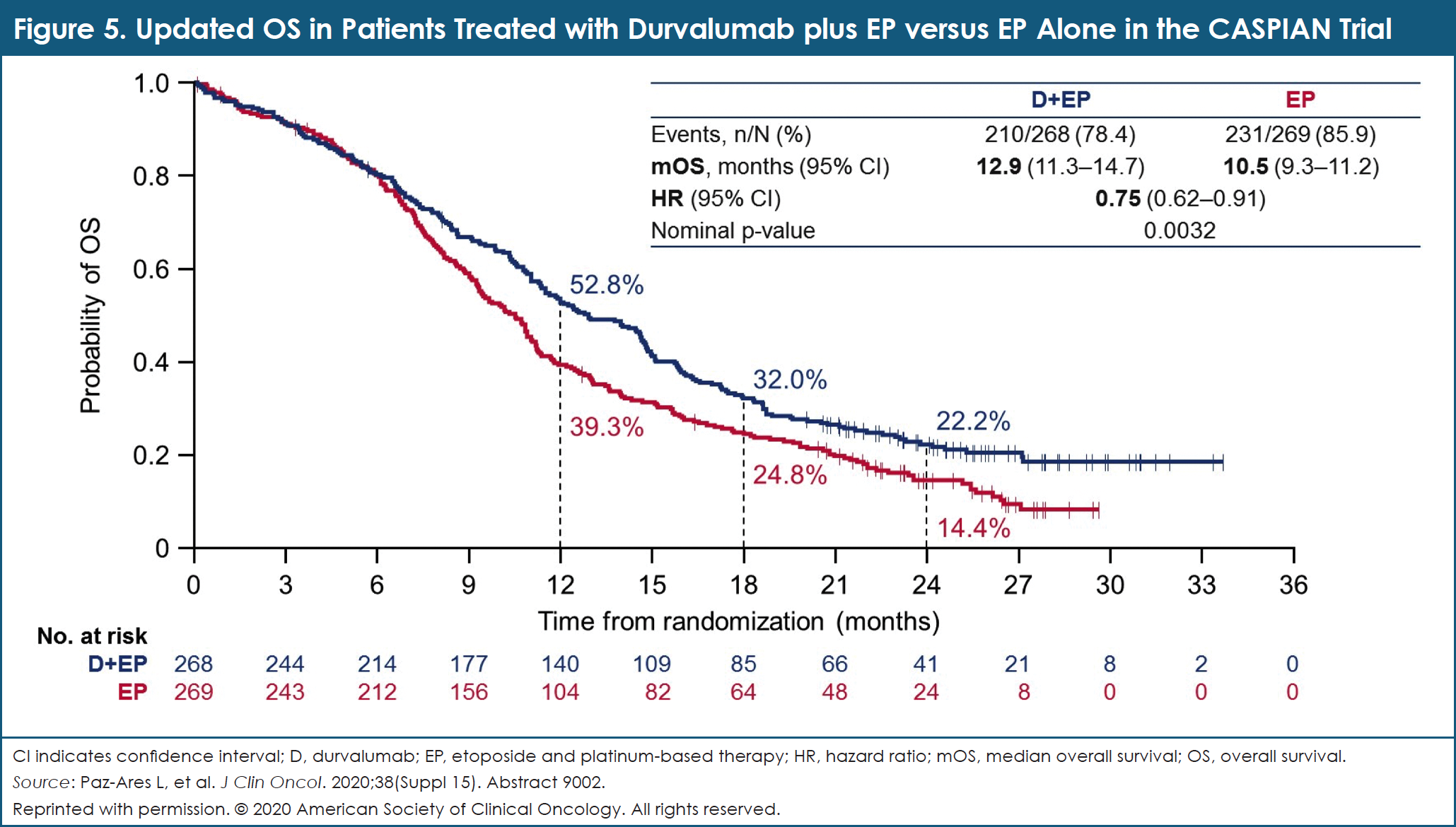

CASPIAN is an open-label, phase 3, randomized, active-controlled, multicenter study of durvalumab (Imfinzi) with or without tremelimumab plus etoposide and platinum-based chemotherapy (EP) for use as first-line therapy in patients with extensive-stage SCLC.23 At the planned interim analysis, the combination of durvalumab plus EP demonstrated a significant improvement in OS compared with the use of EP alone (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.91; P = .0047).24 During the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting, researchers presented results from a planned updated analysis of OS with durvalumab plus EP versus EP only, as well as the first report of results with durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP compared with EP alone.23

Treatment-naïve patients with extensive-stage SCLC and a World Health Organization PS of 0 or 1 were randomized to durvalumab 1500 mg plus EP every 3 weeks, durvalumab 1500 mg plus tremelimumab 75 mg plus EP every 3 weeks, or EP alone every 3 weeks.23 In the durvalumab-containing arms, patients received 4 cycles of EP plus durvalumab with or without tremelimumab, followed by maintenance durvalumab 1500 mg every 4 weeks, until disease progression.23 Patients received 1 additional dose of tremelimumab after EP in the durvalumab-plus-tremelimumab-plus-EP arm. In the EP arm, patients received up to 6 cycles of EP and prophylactic cranial irradiation, at the investigator’s discretion.23 The study had 2 primary end points: OS with durvalumab plus EP versus EP only, and OS with durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP compared with EP alone.23

A total of 805 patients were randomized in the CASPIAN study—268 to durvalumab plus EP, 268 to durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP, and 269 to EP only.23 Their baseline characteristics were generally well-balanced across the 3 treatment arms.23 As of January 27, 2020, median follow-up was 25.1 months (82% maturity).23

The combination of durvalumab plus EP continued to demonstrate improvement in OS compared with EP alone, with an HR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.62-0.91; nominal P = .0032; Figure 5).23 Median OS in these 2 study arms were 12.9 months and 10.5 months, respectively.23 At 2 years, 22.2% of patients taking durvalumab plus EP were alive, compared with 14.4% of those being treated with EP alone.23 Use of tremelimumab with durvalumab plus EP numerically improved OS versus EP alone, but the difference did not reach statistical significance per the prespecified statistical plan.23

Secondary end points included PFS and ORR, with both improving with durvalumab plus EP compared with EP only.23 Confirmed investigator-assessed ORR was similar with durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP compared with EP alone: 58.4% versus 58.0%, respectively.23 Median PFS was also similar with durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP compared with EP only: 4.9 months versus 5.4 months, respectively.23

In the 3 study arms, the incidence of all-cause AEs of grade 3/4 severity was 70.3% with durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus EP, 62.3% with durvalumab plus EP, and 62.8% with EP alone, respectively.23 AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were reported in 21.4%, 10.2%, and 9.4% of patients taking each of the 3 regimens, respectively.23 AEs leading to death occurred in 10.2%, 4.9%, and 5.6% of patients in the 3 groups, respectively.23

The researchers concluded that adding durvalumab to EP demonstrates a significant improvement in OS compared with a robust control arm (EP alone). These data support the use of durvalumab plus EP as a new standard of care for treatment-naïve patients with extended-stage SCLC with the flexibility of platinum choice. No additional benefit was observed when tremelimumab was combined with durvalumab plus EP in these patients. Safety findings in all treatment arms remained consistent with the known safety profiles of these agents.23

Platinum-Doublet Chemotherapy plus Pembrolizumab in SCLC: The KEYNOTE-604 Trial

KEYNOTE-604 is a double-blind, phase 3 study of pembrolizumab combined with EP, compared with placebo plus EP, as first-line therapy for patients with extensive-stage SCLC.25 Patients who were eligible to enroll in KEYNOTE-604 had previously untreated, extensive-stage SCLC, and no untreated CNS metastases. Participants were randomized to receive either pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks or placebo for up to 35 cycles, combined with 4 cycles of standard-dose EP. Patients with a CR or a PR after cycle 4 could receive prophylactic cranial irradiation, at the investigator’s discretion. Patient randomization was stratified by platinum choice (carboplatin vs cisplatin), PS (ECOG 0 vs 1), and lactate dehydrogenase levels (less than or equal to the upper limit of normal [ULN] vs more than ULN).25

The primary end points of KEYNOTE-604 were OS and PFS using RECIST v1.1 criteria and blinded central review in the intent-to-treat population. ORR, DoR, and safety were the secondary end points.25

A total of 453 patients were randomized. Overall, 223 of 228 patients assigned to pembrolizumab plus EP received treatment, and 222 of 225 patients assigned to placebo plus EP received treatment.25 One patient who was assigned to pembrolizumab plus EP received placebo plus EP in error.25 The median age of the patients receiving pembrolizumab plus EP was 64 years, 73.7% had ECOG PS 1, and 55.7% had lactate dehydrogenase >ULN.25 More patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-EP arm than in the placebo-plus-EP arm had baseline brain metastases (14.5% vs 9.8%, respectively).25

At the final analysis, with a median follow-up of 21.6 months, 8.9% of patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-EP arm and 1.4% of those in the placebo-plus-EP arm remained on study treatment. In addition, 11.8% and 14.2%, respectively, of patients in each group received prophylactic cranial irradiation.25

At the second interim analysis, with a median follow-up of 13.5 months, pembrolizumab plus EP significantly improved PFS in the intent-to-treat population (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.91; P = .002; median 4.5 months vs 4.3 months, respectively).25

At the final analysis, pembrolizumab plus EP prolonged OS in the intent-to-treat population, but the significance threshold was not met (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.64-0.98; P = .016; median 10.8 months vs 9.7 months, respectively).25 In a post hoc analysis of OS in the as-treated population, the nominal P value was less than the significance threshold (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63-0.97; P = .012).25 Also in the final analysis, ORR was 70.6% with pembrolizumab plus EP compared with 61.8% with placebo plus EP.25 The median DoR was 4.2 versus 3.7 months, respectively.25

The AEs observed were as expected: any-cause AEs were grade 3/4 in 76.7% of patients receiving pembrolizumab plus EP compared with 74.9% of those receiving placebo plus EP.25 AEs led to drug discontinuation of any treatment in 14.8% and 6.3% of patients, respectively.25 Grade 5 AEs, which were related to death, were reported in 6.3% and 5.4% of patients, respectively.25

In summary, as first-line therapy for patients with extensive-stage SCLC, pembrolizumab plus EP significantly improved PFS compared with placebo plus EP. No unexpected toxicities were observed with pembrolizumab plus EP. These data support the benefit of pembrolizumab-containing regimens for patients with extensive-stage SCLC.25

Cediranib plus Olaparib in Patients with SCLC Previously Treated with Platinum-Based Therapy

Olaparib (Lynparza), a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in patients with various types of advanced solid tumors who carry a BRCA gene mutation.26 The investigators explored the antitumor activity of cediranib—an oral vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitor—combined with olaparib in patients with advanced solid tumors, including those with SCLC.27 This phase 2, multicenter, 2-stage study enrolled patients with metastatic SCLC who had been previously treated in the advanced setting with ≥1 platinum-based chemotherapy regimens. Patients received cediranib 30 mg orally once daily plus olaparib 200 mg orally twice daily, until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The study’s primary end point was ORR by RECIST v1.1. Baseline tumor biopsies were obtained to perform biomarker analyses.27

A total of 25 patients were enrolled in this study, with a median age of 67 years (range, 46-79 years) and a median number of previous therapies of 2 (range, 1-5).27 Most of the participants (80%) had platinum-sensitive disease, and approximately half (52%) had been treated with previous immunotherapy.27

Among these patients, the ORR associated with cediranib plus olaparib was 28% (95% CI, 10%-46%).27 Among responders, the median DoR was 3.8 months; 6 of 8 responding patients had an objective response that lasted for >3 months and for up to 10.3 months.27 The rate of disease control (CR plus PR plus stable disease) was 88% (95% CI, 75%-101%).27 The median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI, 2.3-6.2 months).27 Median OS was 5.5 months (95% CI, 3.4-not available).27

Grade 3/4 AEs, regardless of attribution, were observed in 12 of 25 patients (48%).27 Grade 3/4 AEs reported in ≥20% of patients included hypertension (21%), fatigue (17%), and weight loss (13%).27

The investigators concluded that the combination of cediranib and olaparib is associated with promising clinical activity in patients with platinum-pretreated SCLC, with an ORR of 28% in biomarker-unselected patients.27 In some patients, this regimen required prompt initiation of antihypertensives. The AEs were manageable overall.27 Analyses of mutation status in homologous recombination DNA repair genes are ongoing, to explore whether mutational status is correlated with clinical activity.27

Nationwide Genomic Screening Network to Identify Rare Targetable Genetic Alterations in Patients with SCLC

Gedatolisib, a highly potent dual inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, may have an effect on tumors with PI3K/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT)/mTOR pathway alterations.28 Researchers used a nationwide genomic screening network in Japan, known as LC-SCRUM-Japan, to identify patients with relevant mutations and conduct a phase 2 study of gedatolisib.29

A multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 study was carried out to evaluate the efficacy and safety of gedatolisib in patients with advanced SCLC who had genetic alterations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Patients who enrolled in the study had SCLC and targetable genetic alterations that were identified after reviewing data from 154 cancer centers and hospitals in Japan.29 The primary end point of the phase 2 study was ORR; the planned sample size was 19.29

From July 2015 to March 2020, a total of 1035 patients with SCLC were screened.29 Targetable genetic alterations were identified in 263 (25%) patients, including the MYC family (10%), PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (7%), RAS (3%), and EGFR (1.6%).29

A total of 15 patients with genetic alterations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (7 PIK3CA, 7 PTEN, and 1 AKT1 mutation) enrolled in the phase 2 study and were treated with gedatolisib.29 The median participant age was 64 years (range, 52-84 years); 10 patients were male, and 6 patients had received ≥2 previous chemotherapy regimens.29

The ORR associated with gedatolisib therapy was 0%, and the disease control rate was 20%.29 Median PFS was 0.9 months (95% CI, 0.4-3.0 months).29 The median OS was 5.8 months (95% CI, 1.2-15.6 months).29 Only 1 patient with a PTEN I8fs mutation had durable stable disease after treatment with gedatolisib: the PFS in that individual was 6.5 months.29

Overall, 5 treatment-related AEs, including hypertension, hypoalbuminemia, oral mucositis, alanine aminotransferase increase, and creatinine increase, were observed in 4 patients.29

The researchers concluded that use of a large-scale nationwide genomic screening network can be an effective way to identify rare targetable genetic alterations, despite the fact that this phase 2 study did not demonstrate the clinical benefit of gedatolisib for patients with advanced SCLC who had genetic alterations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway.29

Large-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

Retrospective Assessment of Immunotherapy in Patients with Large-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung are a distinct subgroup of lung cancers that are inherently graded, as they are classified with low-grade typical carcinoid, intermediate-grade atypical carcinoid, and high-grade large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and SCLC.30 During the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting, a retrospective assessment of treatment for patients with LCNEC suggests a role for immunotherapy.

LCNEC is a rare lung cancer with features of both SCLC and NSCLC. No large prospective trials define optimal treatment for patients with either localized or advanced LCNEC.31

Using the National Cancer Database, researchers evaluated data from patients with metastatic LCNEC who were diagnosed from 2014 to 2016 and whose data included ≥30 days of follow-up.32 Demographic data included age (20-69 years vs ≥70 years), sex, race (white vs others), insurance status (uninsured vs others), setting of care (academic vs others), Charlson/Deyo score (0 or 1 vs 2 or 3), the presence of brain metastasis (yes vs no), and the presence of liver metastasis (yes vs no).32

Information regarding patients’ treatments for LCNEC was limited to their first course of therapy, including surgery for primary lesion (yes vs no), radiation (yes vs no), chemotherapy (yes vs no), and immunotherapy (yes vs no). Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests.32

Data were collected for 661 patients with LCNEC, including 37 individuals who were treated with immunotherapy.32 No significant association between the use of immunotherapy and demographics was observed, with the exception of use of chemotherapy (P = .0008).32 Chemotherapy was administered to 92% of patients who received immunotherapy and to 65% of those who received nonimmunotherapy treatments.32

The use of immunotherapy for LCNEC was associated with significantly improved OS (P = .017).32 Landmark analysis in the immunotherapy group revealed 12-month and 18-month survival rates of 34% and 29%, respectively.32 In the nonimmunotherapy group, rates were 24% and 15%, respectively.32

Multivariate analysis demonstrated that female sex, the presence of liver metastases, surgery, the use of chemotherapy, and the use of immunotherapy were all significantly associated with improved survival in patients with LCNEC.32

Based on results of this retrospective study that utilized a large cancer database, the investigators suggest that the use of immunotherapy may improve OS in patients with LCNEC. They recommend prospective clinical studies for further validation of the benefit of immunotherapy in patients with this rare pulmonary tumor.32

Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a relatively rare, but aggressive form of cancer that arises from the membrane covering the lungs and the inner side of the ribs (ie, the mesothelial surfaces of the pleural cavity). MPM often results from exposure to asbestos.33 During the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting, researchers shared data regarding an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen and the use of immunotherapy in patients with MPM.

Weekly Epirubicin as Second-Line Therapy for Patients with MPM

Treatment options are limited for patients with MPM who experience disease progression after treatment with first-line pemetrexed-based chemotherapy.34 This retrospective study evaluated whether, in the age of immunotherapy, a “gentler” chemotherapy—that is, weekly epirubicin—has clinical utility in the second-line treatment of elderly patients with MPM.34

From July 2015 to March 2019, a total of 98 patients were enrolled in this study and were eligible for analysis.34 Patients needed to have histologically confirmed unresectable MPM to qualify for the study. Their histology included epithelioid (N = 86), sarcomatoid (N = 7), and biphasic (N = 5).34 Doublet therapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed was administered in 70 patients, whereas the other 28 participants received gemcitabine monotherapy in the first-line setting.34

A quality-of-life questionnaire was administered, and a geriatric comprehensive assessment was performed for each patient. Epirubicin was administered on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days, until disease progression or intolerance.34 The primary study end point was PFS; secondary end points included ORR, quality of life, and OS.34

Of the 98 eligible patients, 71 were male and 27 were female.34 The median participant age was 78 years (range, 72-86 years), and patients’ PS ranged from 0 to 2.34 The participants received a median of 5 cycles of epirubicin (range, 2-16 cycles).34 Overall, 3% of the patients required dose modification.34

Median PFS for all evaluable patients was 7 months (range, 3-16 months), and the ORR was 17% (all PRs).34 Stable disease was observed in 44% of participants, and 39% of the patients had progressive disease.34 Median OS was 11 months (range, 5-22 months).34

No life-threatening AEs were reported, and no grade 3/4 toxicities were observed.34 Neutropenia (grade 1/2) was observed in 40% of patients, fatigue (grade 2) in 32%, nausea (grade 1) in 20%, liver toxicity (grade 1/2) in 10%, and thrombocytopenia (grade 1) in 9%.34

The researchers concluded that in the era of immunotherapy, weekly epirubicin can be considered a safe and effective second-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with MPM.34

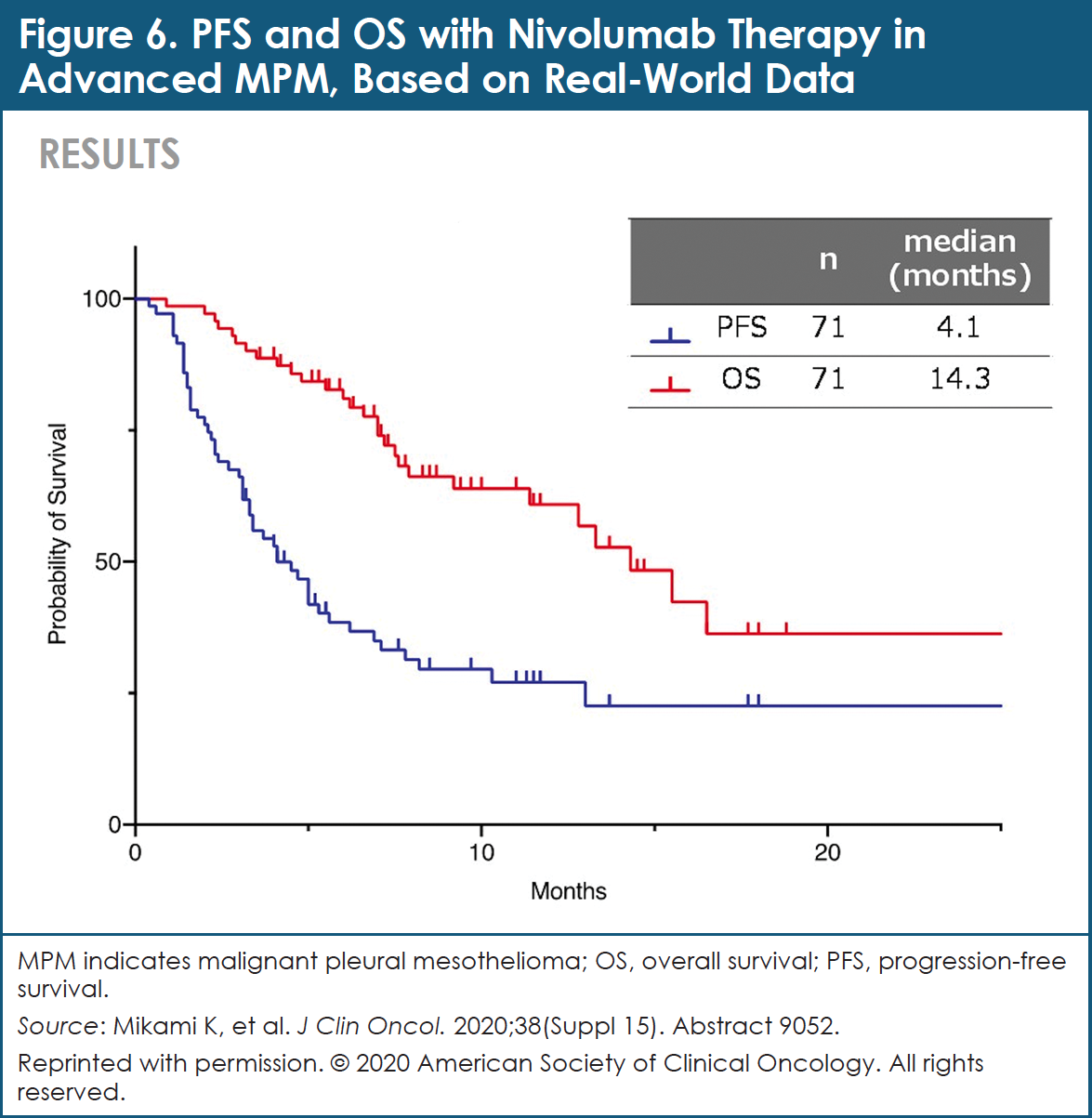

Real-World Data for NIVO in Patients with MPM

Historically, the standard treatment for patients with advanced MPM included cisplatin plus pemetrexed.33 NIVO, an anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody, demonstrates efficacy in patients with pretreated MPM and has been authorized for use in Japan.35,36 Data supporting the efficacy and safety of NIVO in patients with MPM are limited, however, with only 34 patients evaluated in the MERIT trial.36 To supplement these data, investigators accumulated real-world efficacy and safety data for NIVO in patients with advanced MPM.37

A total of 79 patients with MPM who were treated between August and December 2018, including 63 males and 16 females, were included in this retrospective analysis.37 Most of these patients (62 of 79) had an ECOG PS of 0 to 1; 5 participants had an ECOG PS of 3.37 NIVO was administered as second-, third-, and fourth-line or later treatment in 50, 15, and 14 of these 79 patients, respectively.37

Among 71 patients who were examined for efficacy, the response rate associated with NIVO therapy was 26.8%, and the disease control rate was 66.2%.37 By histology type, response rates and disease control rates were 22.8% and 64.9%, respectively, for the epithelioid type; 55.6% and 88.9%, respectively, for the sarcomatoid type; and 20.0% and 40.0% for the biphasic type, respectively.37 Median PFS was 4.1 months, and median OS was 14.3 months (Figure 6).37

The efficacy of treatment with NIVO was analyzed based on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in the peripheral blood.37 Median PFS and median OS in the NLR ≥3.0 group were 3.7 months and 15.5 months, respectively.37 For patients in the NLR <3.0 group, median PFS and median OS were 5.0 months and 14.3 months, respectively.37 No significant differences in response rate, PFS, and OS were observed between the NLR <3.0 group and the NLR ≥3.0 group.37

Hypothyroidism (grade 1 or 2) was reported in 11 of 79 patients, fatigue (grade 1 or 2) in 11 of 79 patients, renal dysfunction (grade 1 to 4) in 6 of 79 patients, loss of appetite (grade 1 or 2) in 3 of 79 patients, rash (grade 1 or 2) in 3 of 79 patients, pneumonia (grade 2 or 3) in 2 of 79 patients, and hypopituitarism (grade 2 or 3) in 2 of 79 patients.37

The investigators concluded that this retrospective study of real-world patients demonstrates that the effectiveness and safety of NIVO for individuals with pretreated MPM were similar to the findings from the MERIT study. NLR is not a predictive biomarker of the effect of NIVO therapy in patients with MPM. PS is an independent factor that contributes to PFS and OS in patients with MPM; NIVO should be administered at a time when PS is favorable.37

Smoking Cessation

It is well understood that tobacco smoking profoundly enhances a person’s risk for lung cancer. Data from presentations at the ASCO 2020 Virtual Meeting suggest that smoking cessation affects treatment outcomes in patients with lung cancer, regardless of the timing relative to lung cancer diagnosis.

Smoking Cessation and Lung Cancer: Recent Quitters Benefit, Too

Although the time of lung cancer screening offers a teaching opportunity, uncertainty remains about the nature of smoking cessation benefits for patients who have smoked for a lifetime. Researchers used the International Lung Cancer Consortium database to determine whether time since smoking cessation prior to lung cancer diagnosis is associated with improved OS and lung cancer–specific survival.38

Analysis was conducted using data available from 17 International Lung Cancer Consortium studies regarding time since smoking cessation, in order to estimate survival.38 Of 34,649 patients in the database, 41% were current smokers, 41% were ex-smokers, and 18% were never smokers at the time of lung cancer diagnosis.38

Ex-smokers (adjusted HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.86-0.91) and never smokers (adjusted HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80) demonstrated improved OS compared with current smokers.38 Among ex-smokers, those who quit within 2 years before their diagnosis (adjusted HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82-0.94), between 2 and 5 years before their diagnosis (adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.77-0.90), and >5 years before their diagnosis (adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.76-0.84) had improved OS compared with current smokers.38

Sensitivity analysis showed a trend toward improved lung cancer–specific survival among those who quit smoking within 2 years before their diagnosis (adjusted HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86-1.05) and those who quit 2 to 5 years before their diagnosis (adjusted HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.83-1.04).38 In contrast, patients who quit >5 years before their diagnosis had significantly improved lung cancer–specific survival (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.92).38

To represent individuals who undergo lung cancer screening, researchers analyzed data from patients with 30+ pack-years. Associations between time since smoking cessation and survival were meaningful: patients who quit smoking <2 years before their diagnosis improved their OS by 14% (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.80-0.93).38 Those who quit 2 to 5 years before their diagnosis improved their OS by 17% (adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.90). Individuals who quit >5 years before their diagnosis improved their OS by 22% (adjusted HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.74-0.83), compared with current smokers.38

In patients with <30 pack-years, a trend toward better OS was observed among those who quit within 2 years (adjusted HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-1.02) and among those who quit in 2 to 5 years (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-1.01).38 Patients who quit smoking >5 years before their lung cancer diagnosis improved their OS by 23% (adjusted HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82).38

Among ex-smokers, the risk for death was reduced by 12% in patients who quit within 2 years of their diagnosis, by 17% among those who quit 2 to 5 years before their diagnosis, and 20% among those who quit smoking >5 years before their diagnosis.38 For lung cancer–specific survival, the benefit was significant only for those who quit smoking >5 years before their diagnosis compared with patients who smoked at the time of lung cancer diagnosis.38

These data suggest that convincing patients who undergo lung cancer screening to quit smoking at any point of their trajectory—even within 2 years of lung cancer diagnosis—improves their OS. Lung cancer–specific survival benefit was present beyond 5 years of quitting. These relationships are independent of pack-years and age and were observed across all disease stages and other prognostic variables.38

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. September 12, 2018. www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed June 14, 2020.

- American Cancer Society. What is lung cancer? Updated October 1, 2019. www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/what-is.html. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: lung and bronchus cancer. April 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed June 25, 2020.

- Hellmann MD, Paz‑Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020-2031.

- Ramalingam SS, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab + ipilimumab versus platinum-doublet chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: three-year update from CheckMate 227 Part 1. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9500.

- Bristol Myers Squibb. Three-year data from Checkmate-227 confirm durable, long-term survival benefit for Opdivo (nivolumab) plus Yervoy (ipilimumab) vs. chemotherapy in metastatic first-line non-small cell lung cancer patients with PD-L1 ≥1%. May 13, 2020. Press release. https://news.bms.com/press-release/corporatefinancial-news/three-year-data-checkmate-227-confirm-durable-long-term-surviv#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20three%2Dyear%20outcomes%20from,to%20deliver%20deep%20and%20durable. Accessed June 18, 2020.

- Reck M, Ciuleanu T-E, Cobo Dols M, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) + ipilimumab (IPI) + 2 cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy (chemo) vs 4 cycles chemo as first-line (1L) treatment (tx) for stage IV/recurrent non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): CheckMate 9LA. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9501.

- Ready N, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 568): outcomes by programmed death ligand 1 and tumor mutational burden as biomarkers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:992-1000.

- Gainor JF, Schneider JG, Gutierrez M, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) with two cycles of chemotherapy (chemo) in first-line metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): CheckMate 568 Part 2. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9560.

- Pathak R, Lopes G, Yu H, et al. Comparative efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy versus immunotherapy alone in the front-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9552.

- Luo J, Bandlamudi C, Ricciuti B, et al. Long-term responders to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9549.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Memon D, et al. Acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9621.

- Harjunpää H, Guillerey C. TIGIT as an emerging immune checkpoint. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;200:108-119.

- Rodriguez-Abreu D, Johnson ML, Hussein MA, et al. Primary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, phase II study of the anti-TIGIT antibody tiragolumab (tira) plus atezolizumab (atezo) versus placebo plus atezo as first-line (1L) treatment in patients with PD-L1-selected NSCLC (CITYSCAPE). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9503.

- Tsurutani J, Iwata H, Krop I, et al. Targeting HER2 with trastuzumab deruxtecan: a dose-expansion, phase I study in multiple advanced solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:688-701. Erratum in: Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1078.

- Smit EF, Nakagawa K, Nagasaka M, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201) in patients with HER2-mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): interim results of DESTINY-Lung01. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9504.

- Käsmann L, Eze C, Taugner J, et al. Implementation of durvalumab maintenance treatment after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in inoperable stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)–a German radiation oncology survey. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9:288-293.

- Shukla N, Althouse SK, Sadiq AA, et al. The association between immune-related adverse events and efficacy outcomes with consolidation pembrolizumab after chemoradiation in patients with stage III NSCLC: an analysis from HCRN LUN 14-179. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9032.

- Cortés ÁA, Urquizu LC, Cubero JH. Adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: state-of-the-art. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:191-197.

- Herbst RS, Tsuboi M, John T, et al. Osimertinib as adjuvant therapy in patients (pts) with stage IB-IIIA EGFR mutation positive (EGFRm) NSCLC after complete tumor resection: ADAURA. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract LBA5.

- Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1070-1076.

- Chang JY, Lin SH, Yao L, et al. I-SABR phase II randomized study of nivolumab immunotherapy and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in early-stage NSCLC: interim analysis adverse effects. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9035.

- Paz-Ares LG, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab ± tremelimumab + platinum-etoposide in first-line extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC): updated results from the phase III CASPIAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9002.

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al; for the CASPIAN Investigators. Durvalumab plus platinum–etoposide versus platinum–etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1929-1939.

- Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, et al. KEYNOTE-604: pembrolizumab (pembro) or placebo plus etoposide and platinum (EP) as first-line therapy for extensive-stage (ES) small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9001.

- Caulfield SE, Davis CC, Byers KF. Olaparib: a novel therapy for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2019;10:167-174.

- Kim JW, Hafez N, Soliman HH, et al. Preliminary efficacy data of platinum-pretreated small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cohort of NCI 9881 study: a phase II study of cediranib in combination with olaparib in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9065.

- Tarantelli C, Lupia A, Stathis A, Bertoni F. Is there a role for dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors for patients affected with lymphoma? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1060.

- Udagawa H, Ikeda T, Umemura S, et al. Phase II study of gedatolisib for small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients (pts) with genetic alterations in PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway based on a large-scale nationwide genomic screening network in Japan (EAGLE-PAT/LC-SCRUM-Japan). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9064.

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al; for the WHO Panel. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1243-1260.

- Glisson BS, Moran CA. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: controversies in diagnosis and treatment. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:1122-1129.

- Komiya T, Powell E. Role of immunotherapy in stage IV large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9060.

- Cinausero M, Rihawi K, Sperandi F, et al. Chemotherapy treatment in malignant pleural mesothelioma: a difficult history. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 2):S304-S310.

- Bollina R, Belloni P, Pelliccione M. A gentle therapy: weekly epirubicin, as second-line treatment in elderly patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9053.

- Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb. Opdivo approved for supplemental applications for expanded indications of malignant pleural mesothelioma and adjuvant treatment of melanoma, change in dosage and administration (D&A) of single dosing regimen, and expanded indication of renal cell carcinoma in Opdivo and Yervoy combination therapy. August 21, 2018. Press release. www.ono.co.jp/eng/news/pdf/sm_cn180821.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2020.

- Okada M, Kijima T, Aoe K, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of nivolumab: results of a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, Japanese phase II study in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MERIT). Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5485-5492.

- Mikami K, Yokoi T, Takahashi R, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab for malignant mesothelioma in the real world. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 9052.

- Fares AF, Jiang M, Yang P, et al. Smoking cessation (SC) and lung cancer (LC) outcomes: a survival benefit for recent-quitters? A pooled analysis of 34,649 International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO) patients. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(Suppl 15). Abstract 1512.